The Estate is named after Ernest Harvist, citizen and brewer of London, who in 1610 bequeathed to the Brewer's Company ‘two closes, or parcels of meadow land called London Fields'. The Estate was transferred to the Commissioners of the Metropolis Roads and built on in the 1860s. (See Streets with a Story, by E, Willats, an invaluable work).

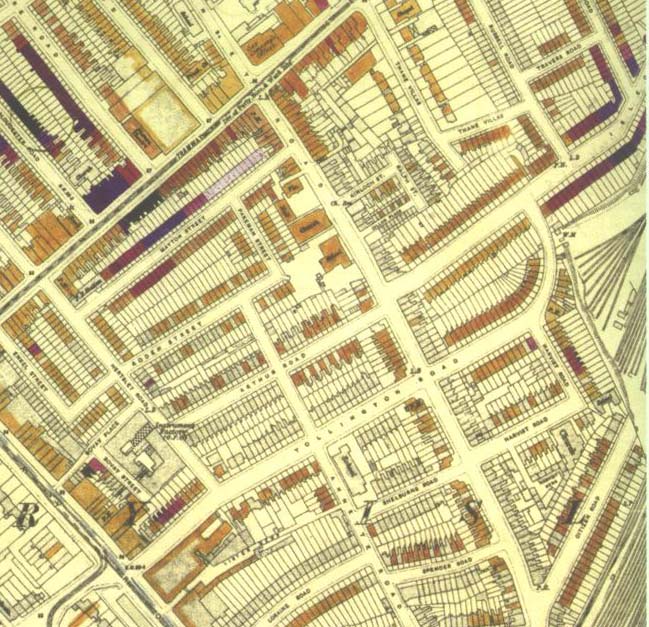

Earlier maps

London Bombing Map of Harvist Estate Area

| Colour Key References | ||

| Black -Total destruction | ||

| Purple - Damaged beyond repair | ||

| Dark Red - Doubtful if repairable | ||

| Light Red - Seriously damaged, but repairable at cost | ||

| Orange - General blast damage, not structural | ||

| Yellow - Blast damage, minor in nature | ||

| O | V1 flying bomb | large circle |

| o | V2 long range rocket. | small circle |

There will be slight variations in the colours because the original maps are old and the colour balance on computer monitors will vary |

||

Uses of the Bombing Map on this website

The Harvist Estate was one of a new kind of building which wa supposed to be quick, economical and efficient. In fact the new designs had several faults which took many years and much treasure to correct.

Slab-built blocks of flats

In the 1950s and 60s a new building idea burst on the scene. Instead of building slowly in the traditional way with bricks, complete walls, with window and door openings already cast into them, floor labs and ceilings panels, would all be built in factories, brought to the site on lorries and assembled on on ready prepared foundations, like Leggo. The whole process of building would be speeded up and the waiting lists for houses be reduced.

In the 1960's there was a serious housing problem. Many houses had been bombed. Many others were in need of repair, or complete demolition. Large numbers of low-income families needed housing as rapidly as possible. Housing numbers were vote winners and people in every party fell for this fool's gold. One can see how the mistakes were made by politicians anxious for headlines. Sadly they were ignorant of both physics and the economic consequences of their scramble for votes.

We will go into the problems as the story unfolds.

Huge blocks of flats were seen as a rapid, factory-built, technological `fix'. Large numbers of people would be housed on small sites Complete walls, kitchens and bathrooms could be ready-built off-site and brought to the building on lorries. It seemed that time and money would be saved, but things were not quite so simple as that.

Huge flats in Hyde Park have uniformed caretakers at the door to forbid entry. Entry-phones to the individual flats help to make them safe. High temperatures in the flats prevent condensation on the walls and the build up of black mould. Good standards of repair and decoration reduce vandalism. Lifts work. Tenants with second homes in the country, are content to do without a town garden. The money which makes the Hyde Park flats work, has not been there for many tower block tenants. Above all, the Hyde Park flats were built in the traditional way: they were not factory-built and made of cold concrete.

Factory built blocks were often expensive to build. They are so heavy that massive foundations are necesssary, especially on London Clay. The deep foundations, or the huge concrete rafts which allow such flats to float on the semi-liquid London Clay, are extremely expensive to make. Because of this foundations cost so much there was not much money left over for adequate fixtures and fittings, so these were often skimped.

Thirdly, many blocks were built with flat roofs. These are a recipe for disaster in our changeable climate. The concrete slabs which form the roofs expand and contract as the temperature changes. The asphalt which is laid on top of the building to keep out the water, melts in summer and cracks in winter. Water seeps in and runs through the electric light fittings in the ceilings. Millions of pounds have had to be spent to put on new sloping roofs, or ‘Upside Down Roofs', where the asphalt is covered with paving slabs to keep it from extremes of temperature in both hot and cold weather. The classic examples of this are the Rhyl Street blocks in West Kentish Town. (see below)

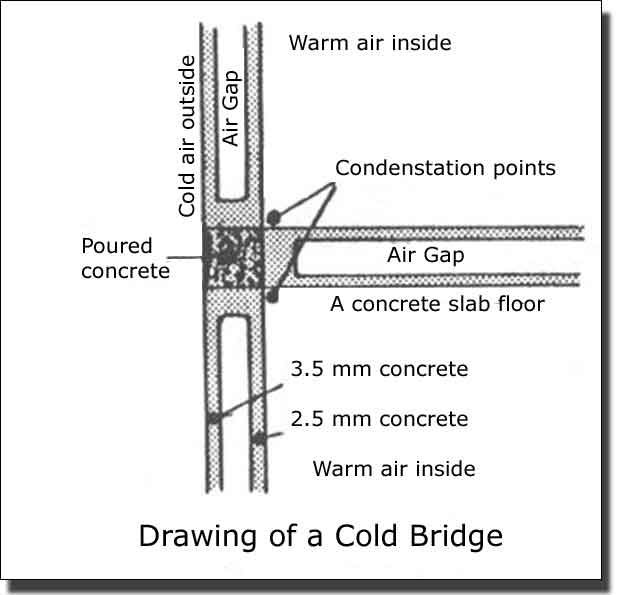

Fouthly, the slabs were fastened together with concrete joints and these formed Cold Bridges (see below)

Islington Council, on the advice of the government, decided to use this form of construction.

31 March 1967The local Islington press announced that 1,500 homes would be built in Hornsey Road. The Harvist Estate would cost £1,500,000 and work would commence in November 1967. The first stages would consist of four blocks 4½ storeys high, a home for the retired, and a day nursery. The land was bought, for £750,000 from Harrow Borough Council which was the holding authority for the Harvist Estate. About 350 families would be displaced when their houses were demolished and need rehousing, but 537 new dwellings, built to a higher standard, would be created. This would be a gain of 187 dwellings. The architects had chosen the Bison Technique of Construction, a pre-fabricated system in which the wall and floor units were constructed in the factory and the erection of these panels would go on all through the winter, regardless of the weather. The 18 storey blocks, in the later stages of the building, would be going on at the rate of at least a floor a week. The firm of Howard Farrow Construction would be responsible for the building work. |

Planning proceeded apace. The Harvist Estate was part of Islington Council's £60 million Housing Programme for 1965-70. The Council planned to produce 8,116 new dwellings in the seven years to 1974.

In April 1967 The North London Press published an artist's impression of the estate and two years later the estate almost ready for occupation.

An artist’s impression of the New Estate

North London Press, April 7, 1967

The Estate was built by May 1969

Four nineteen-storey blocks in the Harvist Estate, containing 435 units, were completed in May 1969 but remained unoccupied because of the worries caused by the Ronan Point Disaster.

The Ronan Point DisasterHere, a faulty gas cooker installed by an amateur gas fitter in a similar tower block called Ronan Point had exploded. It ripped out the side of the building, killing and injuring tenants. This disaster caused general alarm throughout the country. Work on similar blocks was halted, while tenants in other towers became unwilling to live in them. Obviously similar towers needed strengthening, if they were to be occupied at all. The architectural, engineering and political debates became furious. How was this problem to be resolved, not just in Islington but in similar blocks elsewhere? |

The Government offered 40% of the cost of strengthening the buildings, leaving the Local Authorities to pay the remaining 60%, but Islington Council rejected this as inadequate. The Council claimed that they had followed Government advice in using industrial systems of building. All the systems used had been approved by the Government, so the failure could not be Islington's fault. It was not good enough to push off 60% of the strengthening costs, onto local authorities. Islington felt so strongly about, it that they were contributing £500 towards the costs of a court case brought by a number of Local Authorities to test the Government's decision.

The Council had received advice from its consulting engineers on the necessary strengthening. Four blocks in the Harvist Estate, and one at Poole's Park, on which work stopped after the Roman Point disaster, were directly affected. Three other blocks still in the planning stage, at, Newington Green, Mildmay Estate, and Holly Park were also affected, but could be altered on the drawing board. This was relatively easy, but the Harvist towers, which were already built but unsafe, needed expensive remedial work.

There were two ways of solving the problem of possible gas explosion within the buildings. Strengthening the buildings would cost £290, 000, and take fourteen months. Alternatively, gas could be replaced with electricity throughout at a cost of £181,000. This would take only nine months, so the Council l decided to install electricity. Meanwhile they would be losing £100,000 a year in rates and rents while the buildings remained empty.

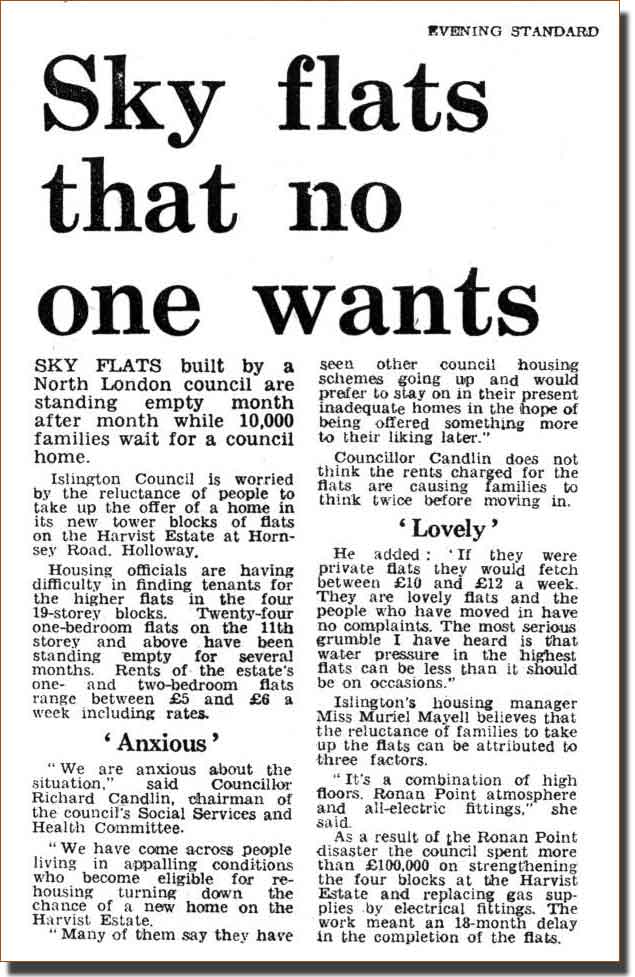

This problem was continuing into the 1970s, as this newspaper article of 14 July 1970 shows.

The Problems with the New Flats

At first tenants were delighted with their new flats. They had bathrooms, often for the first time in their lives, new kitchens, privacy and often more space. Slowly the their attitude changed. They began to smell a musty smell. They found black mould on the outside walls to the flats and round the windiw openings. This was not happenning only in this estate, but in this type of building up and down the country. It seemed to be built into the system. Local Authorities examined the flats. Tenants complained that the visitors from the Council always had bad colds and could not smell the trouble.

14 July 1970

The Islington Gazette and the Evening Standard both reported that people living in slum conditions were refusing to ive in the new 19 storey blacks. They preferred to stay in their inadequate homes and hope to be offered something more to their liking later on. The higher the flats, the more difficult they were to let. Twenty four one-bedroom flats on the 11th storey had been standing empty for several months although the rents were very low.

A Completely Different Problem -

Damp and Cold Bridges.

The Islington Gazette reported damp in Tenby House, on the Harvist Estate. Paper was peeling off the walls; Food cupboards were damp and mouldy. Families suffered from colds and bronchial troubles.

|

|||||

A Council representative said it was due to condensation and water penetration around the window frames. The Council had tried to cure the problem by using water repellant wall covering, but. the tenants had papered over it, destroying it's effect. The tenant, denied having been advised not to paper.

The Council lent the tenant an electric heater in place of her oil heater, to combat the condensation. Heating oil increased the humidity in the room because the end product of burnings parrafin is water vapour and this added to the condensaton on the walls.

The Borough Engineer wrote to the Tenants' Association saying that the Council was considering major work to solve the damp problem. The tenants said another problem was the rain water which collected on the flat roofs and seeped through.

.

2 December, 1977

The Council had had to face a number of insurance claims for damage to furnishings through damp. Four years after the Borough Engineer's letter, and after the Council had been taken to court by a tenant who claimed a 'statutory nuisance' from damp, the Council ordered an £8,000 survey of the flats.

Experiments would be carried out in about 40 flats, some of which would involve increasing the heating. £1000 had been set aside to pay the tenants' increased heating costs.

Insulation

In the end the facts came out. The individual slabs had its insulation were built. Each slab consisted of two layers of concrete with an air gap between them. This air gap was one layer of insulation. Then came a layer of fibre-board which was a second insulation layer. The centre of each panel was quite well insulated. However, the edges of the slabs were made of un-insulated concrete and the separate slabs for the walls and floors were joined by a solid line of un-insulated concrete. This un-insulated concrete was always exposed to the outside air. In winter the cold penetrated deep into the building, cooling the air in the rooms. Water vapour in the rooms condensed on the cold walls outer and black mould developed. This was the cause of the smell and nobody could do anything to prevent it.

Cold Bridges

Cold Bridges

The slabs seem to be insulated but but there were gaps. The edges of the slabs were made of uninsulated concrete and the separate slabs for walls and floors were joined by a solid line of raw concrete exposed to the outside air. In winter the cold penetrated deep into the building, cooling the air in the rooms. There was another layer of insulation board on the inside of each slab but this was not sufficient to prevent the cold from penetrating the line of concrete which joined the slabs.

The Problem of Condensation

Water vapour in the rooms condensed on the cold walls and black mould developed. This was the cause of the smell and nobody cold do anything to prevent it.

High temperatures in the rooms could have held back the damp but the tenant s could not afford this. In adition the end product of North Sea Gas used in the boilers is water vapour and this added to the condensation. Many tenants resorted to paraffin heaters because ethey are cheaper to run, but the end product of burning paraffin is more water vapour. There seemed no way osulated concrete. This was exposed to the outside air. In winter the cold penetrated deep into the building, cooling the air in the rooms. Water vapour in the rooms condensed on the cold walls and black mould developed. This was the cause of the smell and nobody cold do anything to prevent it.

If the rooms were kept warm, the condensation would be less. Many tenants had paraffin heaters because the fuel was cheaper. Unfortunately the end product of burning parafin is water vapour and this increased the moisture in the air, and the condensation. Councils lent the tenants electric heaters and the heating bills went up. Some councils voted extra money to help tenants heating bills. It seemed a vicious circle.

The Cladding of the Harvist Estate, Hornsey Lane

The Estate was factory-built, made of pre-cast slabs and fastened together with concrete joints. These joints had acted a cold bridges, carrying the cold from outside into the inside walls, despite all attempts to prevent it. As described earlier, these cold bridges drew in cold air from the outside and caused condensation on the inside of the walls. This encouraged the growth of black mould on the cold walls and made wallpaper fall off. The Council tried palliative measures but in the end decided to take drastic action. They covered the complete building with a thick protective coating which covered the cold bridges completely. At last the cold could not get in. The flats became comfortable to live in and heating bills fell.

Preparatory work

Before to all the work was started, an earlier semi-underground car park on the site was demolished listed above.

The Cladding

Cladding was an enormous job, so it was done in four phases, by two different building firms: two phases by Llewellyn's and the other two by Murphy's.

Tower Blocks were covered with Externit Resoplan Sheet Rain-Screen Cladding.

This old cold bridges in this tower block have been covered with a rain-shield coating. As a result, the outside cold cannot enter the building and condensation does not result inside.

Coating a building of this size is a serious engineering feat.

Here Llewellyn, one of the contracting firms, has erected two tall girders, triangular in section and braced diagonally with dozens of other triangles, to reach the full height of the building. This type of triangular column is the strongest structure possible for the lowest weight. A scaffolding with surrounding safety barriers was then raised and lowered on the girders, to allow the new windows and panels to be attached firmly to the old building. In this photograph a section of paneling just above the scaffolding and to the right, is being covered. The vertical 50 mm wooden battens have been screwed to the building and 50 mm insulating slabs fixed between them. They will keep the building warm. The outside panels will next be screwed to the wooden uprights, to keep out the rain.

Strong, careful fixing of the panels is vital, as was shown with the cladding of the Mornington Crescent Towers, in Camden Town, North London. Three tower blocks at Mornington Crescent were protected by metal panels, with insulation below. They looked splendid and were much admired. Suddenly protective scaffolding appeared at first floor level, all round the three buildings. Panels had started to fall off and the occupants below had to be protected as they entered and left the towers.

A similar cladding problem at Mornington Crescent

Unfortunately the square corners of the towers were acting as vertical aeroplane wings. No matter which direction the wind came from, it created a Venturi effect and sucked the panels off. As an aeroplane is forced into the air by its engines, it produces a reduction of pressure on the leading edges of the wings. This lower pressure in front of the wings sucks the aeroplane forward and upwards. This is how the plane flies. Its engines create a Venturi effect which pulls it forward and the careful shaping of the wings also causes the plane to lift and so defy gravity. Strong winds on a corner of a tower block can produce a similar reduction of pressure along this ‘vertical wing' and suck the panels off into the wind. The square corner is not as efficient as a carefully designed wing, but an 80 mile per hour wind can exert terrific force on a loose panel.

The Mornington Crescent panels had to be re-secured at the contractor's expense and a new building lesson had been learnt.

To return to the Harvist Estate cladding

The Harvist Estate tower blocks were covered with panels of Externit Resoplan sheet rain-screen cladding. These panels have an insulation system built into them, so that the panels both throw off rain, and also insulate the building from cold. The panels are supplied in different colours, in this case white and grey, to allow architects to use them in a decorative manner and also to reduce the apparent bulk of the buildings.

Security in the flats

Problems of security had been growing over the years so the blocks were given new security entrances. Only tenants of that particular block could enter by special cards or codes. At the same time three High-Rise blocks had community facilities provided on the ground floor.

The Low-Rise Blocks

The Low-Rise buildings presented different problems and opportunities. There was not the same danger from high-speed winds, so these blocks were covered with the ‘ Tor coating external system'. This consists of panels of thick polystyrene insulation to cover the old cold bridges and. keep the building warm. Outside this was a rendering which resists rain, gives a hard finish and can be painted.

Security

The problem of security was rather different from in the high-rise blocks. Here the ground floor tenants had their own front doors at street level, so anyone could approach the door. To keep passersby at a discrete distance, ground–floor tenants were given their own garden spaces. At the same time, small single-storey buildings rather like the old 1860s Bye Law Back Additions, were added. These both enlarged the ground-floor flats and also gave the individual gardens some separation from their neighbours. People can still walk between the blocks but at a slight distance, and tenants have their own private spaces.

Leaking Roofs

Slab-built blocks became notorious for their leaking roofs. Asphalt is a liquid which moves very, very slowly. In hot weather it melts and slides down hill. In freezing weather it cracks and so allows water through. Any raised or sloping surface becomes thinner and thinner within a few yearsas the sasphalt warms and moves downwards. With the alternate heating and freezing, asphalt has a life of only about fifteen years. After that, water can penetrate and after a few years Councils became inundated with complaints from tenants.

The Harvist Estate Low-rise Roofs

Three low-rise blocks with their new pitched roofs in various stages of construction.

These three Harvist Estate blocks appear to have been photographed to illustrate the problem of flat roofs and show two solutions used by architects to cure them over the years.

1. The nearest picture shows the original roof. It was built with a gentle slope to direct the rain towards a central valley, and then to drain the water away at both ends. At first the roof was covered with layers of asphalt, but we know that this failed and water came in.

The roof colour shows the first solution which the architects had tried. They painted the asphalt with a white ‘solar paint' which reflects some of the sun's heat, instead of allowing the asphalt to absorb it all. This reflection of solar heat is why ice on mountains suddenly starts melting faster when some of the underlying rock is exposed. The dark rock absorbs more heat from the sun and melting speeds up. So it proved with asphalt. Black asphalt absorbs much more heat than a white surface, so the painting helped, but later the asphalt failed once again. There seemed no easy or lasting solution to flat asphalt roofs in the British climate. Therefore the architects decided to fit sloping roofs on all the low-rise blocks.

2. The centre picture shows the preparation for fitting the pitched roofs. The roofs were given a new asphalt surface as an extra precaution. This was a belt and braces measure but very wise.The central portions still have their solar paint. The right-hand end appears to have had a single layer if asphalt, while the left-hand end has had several coats. The whole roof would have looked like this beore the new sloping roofs were built above. When the asphalting was complete the roof would have been added.

3. The furthest block has been given a new, low-rise roof covered with slates. At last the roofs should stay water tight.

Another solution to leaking flat roofs

The problem was to keep the asphalt away from the heating and cooling of summer and winter. Here Islington Council solved the problem by erecting traditional sloping roofs above the asphalt. Camden Council fitted Upside Down Roofs in their West Kentish Town Estate. In this system the existing slab roofs were given three layers of fresh asphalt with a sheet of thick polythene above it. Then the whole was covered with concrete paving slabs. These protected the asphalt from extreme heat and cold. Wide gutters filled with large flints, were built round the edges to carry away rainwater rapidly in heavy flash storms. The system was ingenious and, so far as I know, worked well.

Other changes to the flats

All the Harvist Estate blocks had new roofs, new windows and new kitchens with mechanical ventilation systems via cooker hoods.

Externally the estate was completely remodeled and landscaped. The trees are now tall and mature so that the surrounding trees form a most attractive landscaped park with pleasant walks and grateful shade in the summer and the immense tower blocks floating above.

The re-cladded Harvist Estate.

Another view across the estate

The photograph shows a high rise block with a low rise one at its feet. The apparent bulk of the high-rise has been reduced to some extent by the uses of grey and white external panels. Often one colour or the other merges with the sky and clouds behind. This cuts up the stiff rectangular blocks above, by changing their shape.

The ground floor flats have new private gardens surrounded by tall brick walls and narrow projecting screen blocks to give privacy, while the double rows of trees give shaded walks for pedestrians. It has all been very carefully designed.

*****

A Different Solution

TRY TO FIND THIS

Camden Town, together with many other boroughs which had invested millions in slab-built blocks, was having similar problems with a slab-built estate in West Kentish Town, (See The Growth of Camden Town, by Jack Whitehead). A completely different and more drastic solution to the problem was adopted from that chosen by Islington, but interesting in its own right.

CLICK for a shortened version of the Camden Solution and BACK.

9 December, 1983

A family of five was living in a one-bedroomed flat on the 13th floor of a tower block. The tenant had urgent medical priority but there were 800 other tenants in the top priority list in the borough. The flat was damp and the Iift frequent ly broke down.

21 November, 1986

A disabled man who had worked for the Council for 20 years and had injured his back while working for them, was stuck on the 16th floor. The Council would give him a ground floor flat as soon as one became available.

Many cases similar to these had been printed in local papers over the years and would continue to be printed.

In the meantime it would be interesting to find out the solution that was chosen for the damp problem. One drastic solution to tower blocks was to demolish them of course. These demolitions provided a spectacular show on many parts of the country.

Other blocks, like the Rhyl Street Estate in West Kentish Town were covered with given a complete outside covering of 50 mm thick woodwool and hqnging tiles. Others were insulated from the outside cold with a thick mortar covering made of thermo-plaster full of polystyrene beads.

See The Rhyl Street Estate in The Growth of Camden Town, and The Mornington Road Tower Blocks in The Growth of St. Marylebone and Paddington, both by Jack Whitehead.

This article was written on 29 August, 1990. Someone else may like to continue it.

|

||||||