Churchyard Bottom Wood, Highgate

Now called Queen's Wood

Between 1860 and 1880 the centre was torn out of the City of London to build sewers, railways and new roads. Houses were demolished without regard for the tenants who had to find whatever accommodation they could elsewhere. Managers went to livo in Kensington and St. John's Wood, while the poorest crowded into the rookeries like Seven Dials and Lisson Grove. For those between, the clerks and skilled workmen, speculative builders put up row after row of terraced villas and Mr Pooter moved into Holloway. The people of Muswell Hill watched houses creep across the fields of Finsbury Park, up Crouch Hill and down the other side, so that by 1880, Crouch End was being developed and there seemed no way to stem the flow. Ten years later the large estates of Muswell Hill were being sold. Upton Farm was sold and the Ecclesiastical Commissioners wanted to develop Churchyard Bottom Wood, now called Queen's Wood. The story would have made an Ibsen play. Two groups of honest, highly motivated people fighting for what they each thought was right. The Ecclesiastical Commissioners on the one hand and the Committee of the Hornsey Charities on the other, both believed they were doing their best for other people, and the public rose against them both in indignation

At that time Muswell Hill Road was a country road, with Southwood Hall at one end and Upton Farm at the other. By 1894, Onslow Gardens was built, Connaught Gardens marked out, and builders were poised to develop the Woodlands estate. Cut out of Churchyard Bottom Wood was a group of tumble-down cottages, on a triangular site. An undated map, held by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners shows six Wasteland Cottages with an opening between them - not a road, not metalled, but a way through to the strawberry beds behind. Further along was another gap which led to footpaths through the wood. These two openings were to be the basis of the plan. The same two gaps and the cleared ground, which was the strawberry field, can be seen in the 1894 map below. They are shown as 'Muswell Hill Cottages' and, quite in passing, Peter Sellers was to live on the same site much later on. To develop the wood as a housing estate, the Commissioners needed to drive two roads through from Muswell Hill Road and build houses along them. The Muswell Hill Road frontage alone would not have provided room for enough houses to make the venture worthwhile.

The land and cottages had been given much earlier as almshouses to house old people and were held on their behalf by the Trustees of the Hornsey Charity Commissioners. By the 1890s the cottages were tumble-down, in need of major repair. Public-spirited, wishing to do the best for their old tenants, the Trustees could not improve them since they had no money. Some years before the Ecclesiastical Commissioners had planned to develop Gravel Pit Wood (now Highgate Wood) as a housing estate, but this had met such opposition that they backed down. Instead, in 1886, they gave all 69 acres woodland to the public. At the same time they offered to sell Churchyard Bottom Wood to Hornsey Urban District Council for £25,000, but this was too much for Hornsey to raise on its own. The Council said that people living outside Hornsey also enjoyed the wood and other authorities should help, but no help was given. In the end the offer fell into abeyance.

Map showing the Muswell Hill Cottages which were the centre of the controversy.

Muswell Hill Road about 1880

It seems probable that these three pairs of cottages

were the ones at the centre of the dispute.

The Ecclesiastical Commissioners wanted to raise money for its church work in Britain and abroad. They considered that they had been given the land to be used for the propogation of religion and if this meant selling off land or woods, it was a lesser evil than restricting the work of the church. They had given Gravel Pit Wood to the public: in its place they would develop Churchyard Bottom Wood.

The Trustees of the Hornsey Charities wanted to produce an income to help their poor people, so they made an offer to the Commissioners. Their triangular piece of land was too awkwardly shaped to be developed economically, but if the Commissioners would grant them some more land to make it into a square site, they would build twenty-five neat villas. These would bring in ground rents of £225 per annum, which could be used to relieve the poverty of Hornsey people. In return they would permit the Commissioners to cut two roads through their land so that the Commissioners could develop the woods.

When this offer became known people immediately reacted with alarm.

On the 16th December 1893 Mr Carvell Williams MP asked in the House of Commons, if the Ecclesiastical Commissioners had consented to sell a strip of land to the Hornsey Charities Trustees on condition that an existing road be widened to 40 feet, whether this was a preliminary to a building scheme and if the House of Parliament would have an opportunity to express an opinion.

Mr Leveson Gower, a Church Estates Commissioner replied',"Yes" to the first part. Mr Carvell Williams, "Do I understand it is the intention to destroy that portion of Highgate Woods by building on it?" Mr Leveson Gower, "No Sir. My Hon Friend must not understand anything of the kind." |

Two days later The Star published an article worthy of any modern tabloid.

The Star 'Parliament must keep a keen watch on those old vandals and confederates of the jerry-builder the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. They are always alienating some piece of land or are favouring the builders as opposed to the general public. The Commissioners would not sell the Churchyard Bottom wood to the ratepayers but now propose 'to open it up' by cutting two wide roads through it in connection with one of their numerous building schemes. Will not someone ask a question in Parliament and check the brick and mortar policy of the Commissioners?' |

By the time this was printed, the question had been asked and the answer was either untrue, or devious. Other papers took up the story. The Times, in a long report, said that the Comnussioners were not prepared to give an undertaking that Parliament, or any other public body, should have an opportunity of considering any scheme for building on the site of the wood.

The situation simmered for eighteen months until the Ecclesiastical Commissioners were forced to open an enquiry, which began at Highgate on 31 May 1895, chaired by an Assistant Ecclesiastical Commissioner. The Inquiry produced a flurry of newspaper letters of which this was the most important.

The Daily Chronicle, 5 June 1895VANDALISM AT HIGHGATE Sir – One of the most lovely bits of woodland in suburan London is threatened. Will you help us to ward off what would be a calamity, not only to the immediate district, but to the whole of densely-populated North London? In no part of the metropolis has the builder been more active than in Crouch End and Hornsey. The beautiful meadows of a year or two ago are now houses and shops. Ballast heaps have taken the place of stately elms and chestnuts, and once pleasant villages are sharing the fate of Stroud Green, Harringay, Finsbury Park, Highbury and Islington. --- ---- The object is the construction of two forty-foot roads through the woods. We in this district know the meaning of forty-foot roads through woods. It means that the woods are doomed. Ten years ago agitation saved the sister-wood of sixty-five acres - The Gravel Pit Woods - and no one who saw the Bank Holiday crowds flocking up the Archway Road from the dreary streets of Holloway, Islington and Clerkenwell, and watched the keen enjoyment of the children and family parties picnicking on the grass and among the trees, could fail to realise the immense boon that the grant by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners of this wood has been to the whole of North London, but the Lower Wood of sixty acres has always been regarded as a natural complement of the other. ---- --- The Ecclesiastical Commissioners own nearly one-third of the large parish of Hornsey. By the liberal expenditure of the ratepayers' money in the opening up of roads and the general development of the district, the value of their property has been enormously increased, and from this unearned increment they each year draw large revenues. Surely the ratepayers whose money has thus aided in creating the immense estate may expect liberal treatment in return. --- Yours obediently, Signed by The Vicar of St James', Muswell Hill, the Minister of Park Chapel, Crouch End, a barrister living in Onslow Gardens and three members of the District Council. |

It was a shot right across the bows of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. Their own religious leaders and the District Council, all up in arms saying in effect that the church was too rich and should be charitable, not greedy. The inclusion of the two clergymen was a shrewd move. Remember to that this was still in the height of the Darwin controversy. Darwin had split belief in the teachings of the Church and many people would have resented the power of the Church from that point of view alone. The Church was not so secure as it pretended to be.

The Evening News, 7 June 1895 said:- "If the Ecclesiastical Comnussioners are not tackled at once, the building octopus will get a grip of the wood which will be very difficult to loosen later on, ---. Therefore it behoves Londoners to be up and doing if they would save one of their most delightful bits of rustic scenery. The public inquiry stands adjourned to Thursday next, and before then something must be done to convince the Commissioners that the citizens of London will not tolerate the confiscation of one of their favourite playgrounds." |

A letter in the Daily Chronicle the next day said:- .... It was with great relief that that the residents, some ten years ago, heard that the purchase of the Upper Wood had been effected; and how delightful a boon this has proved, anyone who visited them can testify, but all who exerted themselves to save these upper woods, which lie on the west side of Muswell Hill road, felt that their victory was incomplete so long as the sixty acres on the east side remained in danger. It is, as it were, an accident that the woods are divided by a broad high road. Can anyone doubt what the effect would be if the Churchyard Bottom Wood were replaced by rows of small villas, each sending out its contribution of smoke and soot? Can anyone doubt, too, the serious difference it would make to the picturesque setting of the purchased woods if a line of staring new houses were to be run up right over against their leafy frontage?' |

This expressed the opinions of many people. In fact, the Gravel Pit Wood, which the writer calls the 'Upper Wood', had not been purchased, but given to the district by the Ecclesiastical Commission, a point they were to reiterate time and again over the years, but most people ignored it. The Commission was not going to give away a second wood whatever anyone said, and held this position to the end.

H.S.Chamberlain, of 5 Cranley Gardens, I know that it is common to speak harshly of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, but as the trustees of a fund they are bound to administer it to the greatest advantage, and therefore, if anything is to be done to save the demolition of the wood, it appears to me that it can only be effected by the purchase of the property from the Comnussioners, who I know, are fully alive to the protection of free and open spaces for the people, and who, I feel sure, would be disposed to treat the matter of a purchase in a free and liberal spirit, as they have already done in the matter of the Shepherd's Cot-field, by granting a lease to the Crouch End Playing-fields Company - a small company in which I own a few shares, a small company which was formed exclusively for the purpose of securing the fields for cricket, tennis etc. (This refers the the Crouch End Playing Fields which had been secured a few years later.) As Chairman of the Muswell Hill Conservative Association, I am constantly in touch with the inhabitants, and I can safely affirm that every person resident in the neighbourhood would do anything in reason to preserve. (All he wanted personally was Charity income to support his poor people. He demanded his acre of land - not a great deal surely - he believed the Commissioners' assurance that the wood was not in danger.) ' Muswell Hill Road was one of the best in Hornsey and would remain equally beautiful, houses or no houses', (and then came the great rhetorical flourish.)'Are the poor to suffer because of the sentimental objections and the hysterical cry of 'wolf just raised by your correspondents? Something must be done and that soon. An acre of back-land added to the charity-estate would make no appreciable difference to the land remaining, while the profit derived from it would succour many poor old and deserving persons in their declining years and enable us to hand over to our successors an estate which in the distant future would be of great value in the rendering of charitable aid to the deserving poor of the parish of Hornsey.' |

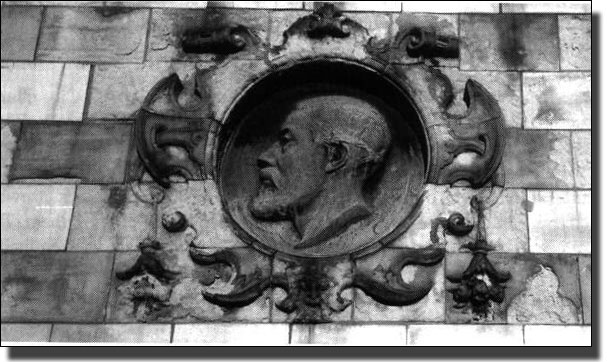

Reading his letter one senses hysteria very near the surface. Why did he think the Commissioners wanted to build a road? Why should they spend all that money if not to build houses? He never seemed to realise that for an acre of land the the whole wood would be lost. But he had been with the problem for a long time. He was the person to whom the Commissioners had made the offer of sale for £25,000 years before and it is his name which is honoured in a plaque on Crouch End Clock Tower for saving the wood, but his trust in the Ecclesiastical Commissioners seems naive. It is sad that at the Inquiry he was to be cast as the devil.

The Inquiry Continued

The adjourned opened in Highgate on 15 June 1895. Expecting a large gathering, the Council Chamber had been changed completely. The usual tables had been removed and the room filled with chairs. By half past seven the room was crowded, with people jostling for seats.

Mr Murray, the Commissioner, said the Inquiry was really a simple one. Hornsey Parochial Charities wished to purchase a piece of land adjoining their charity property at the back. The question was whether the Charity Commission, which controlled all charities, had enough power to stop them. The Church Commissioners were prepared to sell the land at very favourable terms and the income of the Charity would be very considerable increased.

Against this there were three classes of objection.

The original Trust was for the purpose of providing cottages for the Poor, but the trustees were proposing to build villas which would be too expensive for the Poor. However, it was within the power of the Trustees to vary the terms of the Trust, so they could build villas if they thought that the Poor would benefit in the end. The poor people themselves might object, but liberal provisions had already been promised for them. The third objection related to the aesthetic and public side of the question. He took it from what he had read that the Charity Commission ought to interfere to prevent the Ecclesiastical Commissioners from exercising their own discretion in dealing with their own property.

The Inquiry discussed fine points, but the speakers kept coming back to the major problem of preventing any destruction of the wood. The Vestry Clerk of Islington, representing 300,000 people, made a formal protest about any part of the wood, so valuable for the people of Islington and Hornsey being used for private purposes. Mr Wilfred White said that if the Commissioners would give them time they would be able to raise the money to compensate the Trustees. Mr Beaumont said they did not want villas, they wanted cottages for poor people who were being driven out of the district. Others said that there was no money to build cottages to replace the present delapidated ones but villas would be an economic proposition. Others retorted that there were score of villas to let in Highgate. The Wood was sacred. Stick to the question of the Wood. Dr Fletcher said the cry among the working people was that there was nowhere to go. Working people came to him with the cry, "We are driven out of Highgate and are obliged to go to Highgate New Town." If the Muswell Hill Road frontage was sold there was no question but that roads might be cut right through the woods in the direction of Hornsey, but if the Commissioners could not get the land from the Charity Commission they could not cut the road. He was very sure the cottages could be put into a fit state of repair. He was asked by the poor people, by the police and by a number of the working classes to represent these two points, that cottage accommodation was very sorely needed in Highgate and that if they once allowed the land to be sold, there was no telling where the hand of the builder would be stayed. (Loud and prolonged cheers). |

Numerous other people spoke and the Comnussioner summed up by saying that he took it that the prevailing opinion was in favour of retaining the cottages but the meeting should draw no conclusions from what he had said (Groans).

Others said that the Trustees of the Charity had failed in their duties by letting the the cottages fall into disrepair.

Mr H.R.Williams, the Trustee who had written to the paper earlier, said that he had it on the best authority that the Church Commissioners would make no roads whatever and they would not be benefitted one iota by the actions of the Charity Commissioners. Others were far less trusting and the meeting closed after nearly three hours.

Drawn from

Hornsey & Finsbury Park Journal & North Islington Standard report, 15 June 1895).

Another article from an unknown and undated paper says:- 'We are faced with the fact that in Highgate and Muswell Hill there are a number of persons who want the Churchyard Bottom Wood and will not be happy until they have got it - while nobody appears willing to spend a farthing to pay for it. Everyone says it would be a fine thing to have the wood as open space, but everybody thinks it is the duty of someone else to make it one. The Islington Vestry has 'resolved' on the subject, but the Islington Vestry does not offer a penny piece towards the purchase. --- There is no more difficult problem for the community or the individual to solve than how to gain possession of other people's property without paying for it.' |

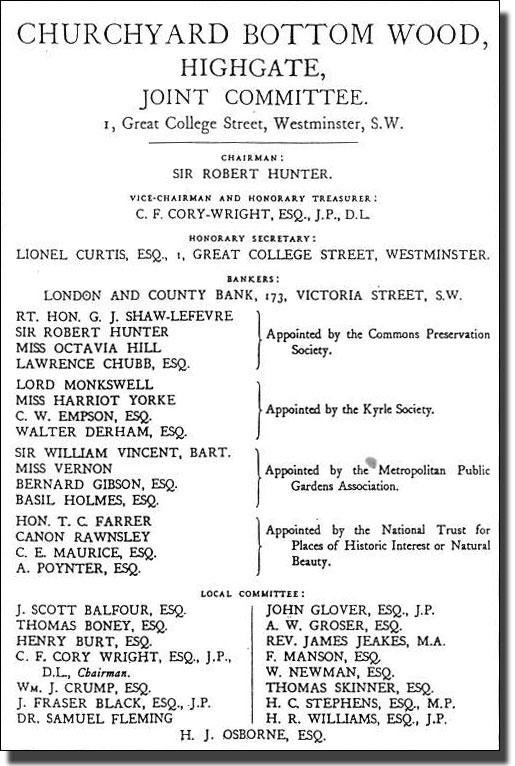

Paying for it was indeed the problem as Churchyard Bottom Wood became the subject of intense local and national debate. A joint committee was formed to raise money to save the wood. On 20 November 1896, C.F.Cory-Wright, Hon Treasurer, wrote to The Standard, a daily paper at that time, appealing for help. He reminded everyone of the danger of losing the wood and said it could only be saved by buying it. The Church Commissioners would sell for £25,000 and an extra (5,000 would be required for fencing and drainage, making a total of £30,000. This was too much for Hornsey Council to raise but they had already voted £10,000 towards the total. The woods were of inestimable value to all of North London so he appealed to public bodies and private people to raise the remaining £20,000. He warned that the present offer from the Church Commissioners was open only to the end of 1898. After that the builders would move in.

The appeal was warmly welcomed by the press. A Private Bill was rushed through Parliament and the Highgate Woods Preservation Act, 1897, became law. The Conunittee now had the right to advertise for contributions towards buying the Wood and preserving it.

In a fairly short time almost all the money was raised, but the last few thousand proved very difficult to raise and the Commissioners' deadline was a matter of weeks away. Mr Cory-Wright wrote pleading for more time but was granted a mere three months and then only if interest at 4 per cent was paid for the extra period on the full sum. In the end the London County Council, which had originally offered £2,500, made this up to £5,000 and the total was reached, but it was a close-run thing.

The Council decided to re-name the Wood as 'Queen's Woods’ in honour of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee and Hornsey put on a fine display of bunting when the Duchess of Albany formally declared the Wood open 'for the free use of the public for ever'.

While the campaign to save Churchyard Bottom Wood was run and directed by local people who felt passionately about this particular piece of woodland, they called on the help and experience of a vast network of people, some of whom had worked together on similar campaigns for over thirty years. The Committee issued an appeal, printed on very good quality paper and bearing some famous names.

The questions of open space and public health were major subjects of the Victorian vision.

The Open Spaces Movement

Octavia Hill, the great housing reformer, who had begun with three old houses in Marylebone, bought for her by Joln Ruskin, had quickly become an expert on housing poor people in the healthiest conditions possible. Her way was to buy leases and then knock down some of the crowded houses in order to bring light and air to the rest, believing that fresh air and sunlight were the the only way poor people could be saved from 'putrid fever. She had learnt this as a child from her grandfather, Southwood Smith, who developed his theories at the Fever Hospital at King's Cross.

He had built the first Industrial Dwellings for poor people and had proved statistically that good air and decent drainage saved lives. Gibson Gardens, in Northwold Road, is a direct outcome of Southwood Smith's ideas. More Information on Gibson Gardens

References to Southwood Smith in this website.

The Importance of Open Air

Open spaces and the opportunity to breathe clean air, were essential for people living in one or two crowded rooms. Octavia Hill took her charges from the Lisson Grove slums, up Fitzjohn's Avenue to Hampstead Heath. She so loved the Fitzjohn's Avenue fields that she tried to buy them as a public park. They were to cost £10,000 and within three August weeks £8,500 had been raised. It needed only the end of the summer holidays and the return from holiday of sympathetic friends and the further £1,500 would have been raised, but the owners suddenly withdrew their offer. Despite all pleading, the fields were covered with large houses.

From this developed the campaign to save Parliament Hill, the next open space northwards from Lisson Grove, buying up fields in the path of the builders to make a permanent cordon sanitalre against the advancing bricks. The Parliament Hill Fields campaign was so successful that the Hampstead Heath Bill was passed and there was money over from the appeal. From this money and the impetus towards open spaces, was to develop the National Trust. Octavia Hill had been interested in protecting areas like Church Bottom Wood for years, so she was a natural ally in the fight to save the Wood.

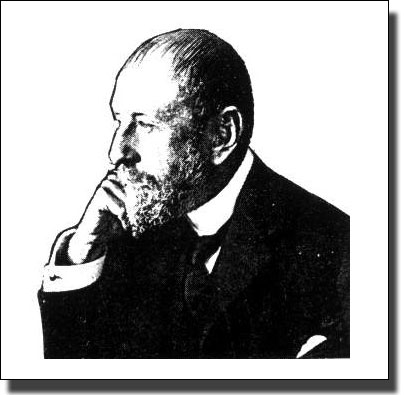

The Commons Preservation Society also, was familiar with this kind of agitation and money collection. They had torn down fencing when lords of the manor had enclosed pieces of common land, leading both legal and illegal battles against the arrogant privatization of land traditionally free. Robert Hunter, their Honorary Solicitor from 1868, was always concerned with securing open spaces, large or small, for the public. He, now Sir Robert Hunter, became the Chairman of the Church Bottom Appeal. The Chairman of the Commons Preservation Society was Mr Shaw-Lefevre MP (later Lord Eversley) who played a big part in this and other campaigns in the House of Commons. Octavia Hill had been involved in their work from about 1875.

At the same time Octavia Hill was campaigning for a Burials Bill.

City churchyards had become so full and such a serious a hazard to health, by contaminating wells from which people drew their drinking water, that City burials were no longer permitted. Instead, cemetries were created on the outskirts of town. Abney Park Cemetary was one of these. There was then a movement to remove the headstones to the edges of the old town cemetries, re-inter the bodies elsewhere and turn the cemetries into gardens and open spaces, instead of building on them. This land in the centre of London was very valuable and speculators were avid to obtain it: Even the Quakers had built over one of their cemetries and threatened to do so again by building over Bunhill Fields. Octavia Hill had a network of allies in a dozen fields, so her help to save the Church Bottom Wood must have been invaluable.

The Metropolitan Gardens Society, set up in 1882, had laid out about two hundred small gardens in city centres by 1890. They later handed them over to the Local Authorities, so their support for the Churchyard Bottom Wood Appeal was assured from the start.

The Kyrle Society is forgotten now, but in its day had great influence on Town Planning and Open Space legislation. The Society had been set up about 1875 for 'the Diffusion of Beauty', to bring colour and interest into the lives of people living in dull, drab surroundings. Bright colour to walls and decoration, good singing, open spaces, Nature, Literature and Art. All these fell within the Society's remit. There was a Decorative Branch, for whom William Morris lectured; a Musical Branch to promote choirs and Happy Evenings for people in local school buildings; and a Literature Branch. The Society appealed regularly by letters in The Times, to 'the richer classes' for books and periodicals to be distributed to boys' and girls' clubs, almshouses and elsewhere. However the Open Spaces Committee was the most active. The very name 'Kyrle' came from Pope's The Man of Ross, the philanthropist who gave his birthplace to the people as a public park.

Sir Rober Hunter

1844-1913

The bas relief of Mr R.H.Williams

on the Crouch End Clock Tower

|