Grazebrook School Walk 1

The Actual Walk

The Route of the Walk laid out on the 1914 Ordnance Survey map. This will allow you to compare what was there in 1914 and what has been changed, or rebuilt at different times since then.

The Route of the Walk laid out on the 1814 Ordnance Survey map.

From the School gates we can see a variety of houses, some old some new. We are going to look at them quite closely. The Bombing map will tell you what happened to the different houses and will help you to notice what has changed since then.

A pair of early Manor Road houses similar to Willow Lodge (shown above).

These are large, generous houses on wide street frontages. One could fit two smaller houses into the same road length. Some houses like these have side entrances but here they have been built over to give another complete stack of rooms. The houses have semi-basements and a flight of steps leading to the ground floor rooms.

|

Each house has a porch with round pillars and Corinthian Capitals. These are the most elaborate of the Greek capitals. In stone, they cost an enormous amount to carve. These ones are in stucco, a mixture of sand, cement and other materials, poured into elaborate moulds. The moulds were themselves expensive to carve, but of course a great number of capitals could be cast from one mould. They were still expensive because the risk of damage was high. Compare these Corinthian capitals with the simple ones to be found elsewhere in the neighbourhood. Cubitt’s ones in Albion Road are particularly plain and economical. The top of the porch has a projecting canopy supported by rows of brackets and dentil work (like rows of teeth). |

| Porch detail showing stucco Corinthian capitals on round pillars. |  |

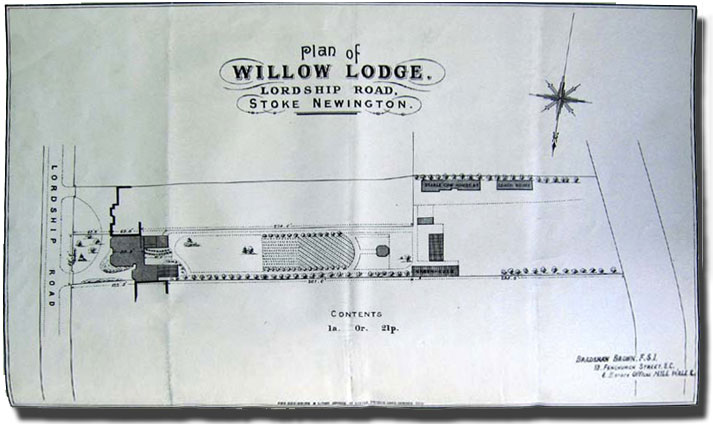

Until about 1850 whole area around the present Grazebrook School site was still fields, as it had been for centuries, but then large houses began to appear. The old curved border of the Crooked Field, which is shown on the Lady Abney map id 1734, was still a field boundary, but Lordship Road and Manor Road had opened the Abney Estate for building. Large houses with long gardens were appearing. There was a house at the corner where the United Reform Church and its Playgroup now stand. Willow Lodge, shown below, was one of these houses. The houses opposite the School are now divided into flats, but once they were single houses with very large gardens behind, tennis courts, conservatories and small orchards.

The plan of a Willow Lodge, Lordship Road, which was typical of the area

The Garden

A stately tennis match. There was room for the garden

and for a tennis court in the grounds of The Willows.

.

.

Restored houses, now blocks of flats, in Lorship Road

Look at the tops of the windows. Some are flat and some are curved. These window heads, which are designed to stop the bricks above from falling down, are called lintels

Lintels

The purpose of lintels is to support the weight of the brickwork over a window or door opening and carry the weight sideways to the brick columns on either side. One can look on a house as a series of brick pillars with windows and doors between. Imagine arranging windows at random over the front of the house. It would look wrong and be most upsetting. We would expect it all to fall down and it would soon oblige.

The architect of this pair of houses used two different sorts of lintel.

A curved brick lintel with stone or stuccoed abutments on each side and a central keystone. An abutment is something that a lintel, or a bridge, can push against. |

This straight lintel is made of wedge-shaped London Stock bricks, elegantly moulded and laid. Together the bricks form a wedge which pushes against the bricks in the house. On either side is a pair if brackets supporting the eaves of the house and the pantile roof above. The original roof would have been in slate. Pantiles were quite rare in England in the Victorian period. The window bars are extremely fine and the window frames have been set behind a layer of brickwork for safety against fire. This means that very little of the wooden window frame shows from the outside and the windows appear very delicate. This post- war extension to the house is built completely differently from the original pair of houses.

|

The lintels here are linked into a curious band of brickwork four courses deep. The bricks are ordinary ones pretending to be wedge shaped, so the effect is far less elegant than the older shaped ones. The windows are shorter and the frames are not covered by a layer of brickwork, so that they look more chunky then the originals.

Chimney pots in Lordship Road houses show how

many fireplaces there are in houses this size.

There are twelve chimney pots for each house. Imagine these houses a hundred years ago, with an army of servants to clean out, relight and carry coals for all these fireplaces every day. In Kitchen Fugue, Sheila Kaye Smith described her late Victorian childhood in a similar house in Sutherland Avenue, W2 in 1885.

HOW THE PROSPEROUS LIVED IN 1885:Sutherland Avenue , PaddingtonIn 'Kitchen Fugue', Sheila Kaye Smith wrote about her Late Victorian childhood in another, but similar road, which had been built in 1885. 'Besides the nursery staff we had a cook, a house-parlourmaid and a housemaid. I do not suppose that anyone today in my father's position would keep more than two maids, or indeed more than one. But in keeping three he was doing no more than most. In Arabella's house there also were three maids, and in every other house from number one upwards to the top of the hill. Forty-six houses - one hundred and thirty-eight maids in white caps and white aprons, print dresses in the morning and black dresses in the afternoon - one hundred and thirty-eight maids, sleeping in basement bed-rooms, eating in basement kitchens, carrying meals up basement stairs - up other stairs as well, for we had all our meals carried up to the nursery - carrying hot water to each bedroom four times a day, carrying coals for half a dozen scuttles, lighting and making up half a dozen fires, cleaning and blackleading half a dozen grates, sweeping carpets on their knees with dustpans and brushes, scrubbing floors, polishing furniture and "brasses" with polish they had to make themselves, and, lighting the gas in every room and pasage when darkness fell, besides all besides the business of cooking and waiting at meals and washing up afterwards - No, I do not think we were over staffed. The house had been built in 1885, and when my parents took possession of it as its first tenants it was regarded as the very latest expression of modernity and domestic enlightenment. It had, for one thing, a "housemaids cupboard" half way up the second flight of stairs, a sensational improvement on those houses where no water at all was laid on above the basement. We had a bathroom, too, and there was a cloakroom with hot and cold water taps on the ground floor. Nothing could be more up to date. 'Kitchen Fugue', published in 1945 |

Post-war houses in Lordship Road

Post-war houses in Lordship Road

These new houses are very simple three-storey cottages with sloping roofs and in a brick which was unusual for London. These liver-coloured bricks are typical of the nineteen sixties and seventies. At that time there was a frenzy of building to house the thousands who had been bombed out, or who wanted to get married and have families. Local Authorities in London, like Hackney or Harringey, each built more houses and flats each month than Local Authorities built in the whole of the country in 2005.

As a result of this flurry of building, there was a national shortage of bricks and types which had never been seen in London before suddenly appeared. All sorts of colours and types were pressed into service. Harlow even had black bricks made partly from coal dust – a most depressing type – but fortunately London was spared these.

Now turn into Lordship Grove and go to the terrace of old houses on the right.

A terrace of Lordship Grove houses in mature London Stock brickwork.

Houses in the New Estate can be seen at the end.

These houses are shown on the 1868 Ordnance Survey map and must be some of the first in the area with Back Additions.

1868 Back Addition Houses in Lordship Grove

These particular Back Additions cannot be seen from the road but are shown on the map and can be seen from inside Churchill Court. You will have seen plenty of them elsewhere.

Back Additions

By the 1860s terraced cottages were being built everywhere, narrow and extremely small. This need for narrow frontages, to keep down the road building costs, conflicted with new health regulations, Landlords wanted short road frontages (which were cheaper) and to build behind, so that the ground that had once been gardens became covered with warrens of interlining tenements. Local authorities had other ideas. They were faced with the problem of bad health. They demanded healthy buildings with through draughts, to blow away some of the germs. At this time they did not know what germs were but they knew that fresh air saved a lot of lives. Up to this time it had been possible for landlords to open rooms out of other rooms, so that inner ones might have had no windows opening to sunlight, or fresh air, Tuberculosis was rife. Streptomycin, our modern cure for Tuberculosis, was not invented until the1950s. When these houses were built people thousands were dying of tubeculosis each year. People needed fresh air and landlords were building unhealthy, airless dens. New bye-laws made by the local authorities, not central government, insisted that every habitable room had to have windows which could be opened to the air and these had to be of a size related to the floor area of the room, This would reduce fevers and contagious disease by allowing the free passage of air into every, room, These regulations led to the Bye-Law House, with its back addition and typical L shaped plan. It gave three thicknesses of rooms with windows to fresh air, instead of the normal two, The design swept the country. |

|

|

Party Walls and the

Fire of London Building Regulations.

A pair of houses which have survived in perfect condition

These houses are in London Stock bricks, containing about 15% of Chalk. The bricks were made in the Thames Estuary, where Chalk and London Clay are found conveniently close together. The mild colour became very fashionable in the late 17th Century, about the time of Swift and Defoe, and London Stocks have been popular ever since. They suit stucco and white paint particularly well. These bricks are almost certainly not real London Stocks but were made from local London Clay in the brickfields on this side of the High Street.

Mylne’s Map of the Geology and Contours of

London and its Environs

Between the houses are party walls designed to prevent fire from passing from one house to the next. By law they had to protrude above the roof, for extra protection, and to be a minimum thickness. This is part of the Fire of London Building Regulations, which were brought in after the Fire of London in 1666.

Why were the Fire of London Building Relations brought in?

And Why Do They Still Control Our Buildings?

In the Great Fire of London, fire which started in one shop spread rapidly from houses to house and street to street until the centre of London was devastated. The danger was not just fire, but the spread of fire. Why did the fire spread so rapidly?.

Wooden Houses and the Danger of Fire

Early cities and towns were built in wood. Amost every one has had a series of disastrous fires. New York, Chicargo and dozens of others have gone up in flames. The Great Fire of London is probably the most famous.

| Before the Fire of London, in AD 1666, almost all the houses were built of timber and thatch. Trees were grown to about 200mm (8 inches) diameter, felled and squared with an adze. This gave posts about 150mrn (6 inches) square and usually about 2-2.5 metres long (6.5-8 feet). Bigger trees could have been grown, but this took a long time, so most trees were cut as soon as they were useable. The length of the trunk controlled the height of the house storeys and also the shape of the buildings. |  |

Life in a Forest Workshop

The timbers were prepared in the forest and then dragged away to be errected

Lopping off the side branches |

Quartering the log with wedges |

Sawing with two handed saw |

Errecting a building |

|

If two timbers were placed end to end, the joint where they met became permanently damp from the rain and then rot set in. Therefore upper storeys jettied out beyond the lower ones so that rain could drip off. This and the thatched roof, made it easy for a fire to spread. Cities were enclosed by city walls, so space was limited and streets were narrow. The jettied houses were so close together that people coud shake hands across the street from the upper floors. The streets became narrow wooden tunnels and fire could spread rapidly from one street to the next. Wooden cities all over the world have had devastating fires. |

|

After the Fire of London, new Building Regulations were imposed and they, repeatedly updated, have governed London building ever since. All houses were to be in brick or stone; no wooden eaves were allowed - roofs were pushed back behind brick parapets; wooden window frames were reduced and later recessed behind brick; thatch was forbidden; party walls between houses had to project above the roof and be thick enough to withstand at least two hours of fire, to give the neighbours a chance of extinguishing the blaze. The face of London was changed for ever.

The Result of the Fire

A pree 1666 wooden house |

A post 1666 brick house with the roof behind a parapet |

To return to these houses in Lordship Grove

The doors, with square transoms above to let light into the hallways, and the door surrounds in stucco, are all simple and quiet. The windows have the majority of the frames hidden by a layer of bricks, so little is showing. The sash windows have large panes and thin glazing bars, giving the whole a delicate appearance. These sash windows can be opened to any position and they will stay there. They do not fall down by gravity because each sash has a balancing weight on either side to hold it still.

There are two different kinds of lintels. The top ones are curved and use ordinary bricks. The lower ones are straight and use special wedge-shaped bricks. The slate roof has a low slope, which gives a good run off but keeps the timber lengths and the number of slates quite small. This slope was found to be an efficient use of materials and can be found all over Victorian London.

|

This is a typical London County Council name plaque. One can often pick out an L. C. C. estate by this type of plaque. |

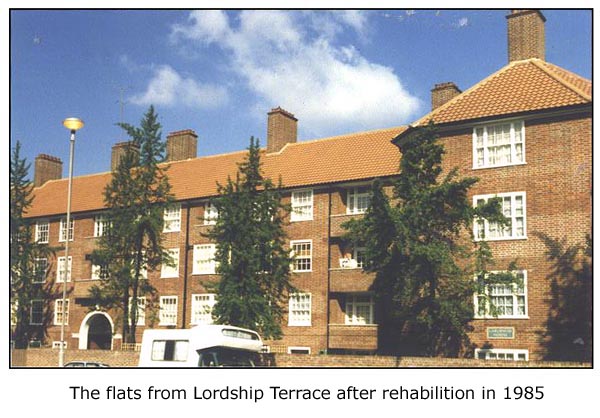

These flats were the first Local Authority flats in Stoke Newington. They were built in 1935 and reconditioned fifty years later in 1985. They were very highly praised when they were first built and a part of a very long story. You will want to explore this back in the classroom, either before the Walk or afterwards. It is too long to take in on the pavement.

The Slum Clearance Movement in the Nineteen Thirties.

To return to the flats.

They are in an attractive orange/red brick with red pantile roofs. They have tall chimneys because the flats were built with coal fires, but these chimneys are now capped off and have become mere reminders of the past, like the human appendix.

There is a central entrance with a large Roman arch. Beyond there is the central courtyard and a sense of privacy. The wooden window frames are not hidden behind a layer of brick so they look much heavier and not delicate like the ones we saw in Lordship Grove.

The windows have double sashes. Each sash can be lifted to any position and it will stay there because it is balanced. On either side is a cord which runs over a pulley. On the other end of each cord is a heavy weight. When the window is opened, the weight rises or falls and so balances the weight of the window sash and it stays still.

One sash is in front of the other. Which one and why?

Now cross Manor Road and walk along the other side of the road towards School.

Manor Road Houses

These houses in Manor Road are much smaller than those we saw earlier and those in Stoke Newington Church St. These have three storeys, with quite tall windows in the first floor and smaller ones at the top. These houses have no attics and no basements. At at the time they were built there may have been one servant living in, but not more. Compare these Manor Road houses with the houses at 207-223 Stoke Newington Church St. which have four storeys and a basement. The actics in Chuch St., have tiny windows and were for live-in servants. The basements, which we can see under the front stairs are sunk well into the ground. The larger houses in Manor Rd and the sort of people who would have lived in them, we met earlier in this walk. The people who lived in Church St., may have been even more properous - they would certainly have had three servants living in the basements and attics. But in Manor Rd there are no basements!

|

|

Why are there No Basements?

The Stoke Newington Church Street houses are built on Gravel, with a layer of London Clay below. Gravel drains well. The rain water can flow through the gravel and away, leaving dry basements.

There was probably Gravel on the top of the London Clay long ago north of Church Street , but if so, the Hackney Brook and all its tiny tributaries swept it away long ago. Manor Road is down to the London Clay and one cannot build basements. If you built a basement in London Clay it would fill up like a swimming bath.

Manor Road Houses

This type of house continued down the slope of Manor Rd. The 1914 map shows them running right up to the large houses still standing next to the school. A long line of them were destroyed during the bombing and the School was built on the site

The Site of Grazebrook Primary School

The School is a bungalow building, so low that it is hidden by the trees and hedges.

The last of the early houses in Manor Road

Here we can see the last house left after the bomb destroyed the houses which are now the site of Grazebrook School . This houses was one of a semi-detached pair, like the pair next door. The red house must have been repairable, so they demolished the other half and rendered the end to make it waterproof, did whatever repair was necessary and it has been lived in ever since.

Now walk along the side of the School to the gate.

There may be some local people who remember the War. If you can find them, they may have some interesting stories to tell.

| Grazebrook Primary School |