The Origins of the Census in 1801

The Census was first taken in 1801 but the returns were made by the local vicar, or some other prominent person. People did not fill in their own returns. Many could not have done so as they could not read or write. In any case the Government was not much interested in individuals. It just wanted how many men there were in four different groups. These were:-

| People of independent means Professional Engineers Agricultural Labourers |

Britain had recently lost the American Colonies and America had declared her Independence in 1776. Now, less than thirty years later, there was a threat that America would develop into a great manufacturing nation, as indeed she did, and Britain wanted to prevent engineers from emigrating to America. Whitney, the founder of the great American agricultural machinery firm and eventually Pratt and Whitney engine manufacturers, was one of the thousands who emigrated. To do so he had to dress up in an agricultural smock and left England carrying a shepherd's crook.

The local vicar sent in his census returns to London in the four categories. They were compiled as a set of statistics and the originals were thrown away. Therefore we have no details about individuals in the early days. In 1841 the first Census Returns showing individual households and their members, with ages and other details was taken. These are the first people we can research as individuals. Slowly extra questions were asked so that later returns tell us more and the census returns opened a new source of study.

Using the Census

Today the Census Returns are readily available on the internet, so schools can study the histories of their local streets easily. They may offer surprises because no two areas are quite the same and some offer windows into very different lives.

The Coppetts Road Estate, in Muswell Hill for example, started in Coppetts Road and gradually spread back into what had been the old Middlesex Forest, untouched for centuries. Building started in 1924. soon after the end of the First World War, as part of Lloyd George’s campaign for ‘Homes for Heroes’. Thousands of families were in desperate need of houses and this estate was designed to take some of them.

In ‘The Growth of Muswell Hill’ I said that it was like the resettling of a Roman legion. Sometimes a legion took over an old established valley, driving away the inhabitants and taking their farms. Ovid and his neighbours were faced with this, but as a famous poet he had enough influence in Rome to fend them off. Where the legion went I do not know.

Alternatively, a legion might be planted on virgin fields, the borders of the Empire. This is what happened in Muwell Hill, which was then near the edge of London. House after house held returned servicemen. It was a camp of returnees and the one subject never mentioned was the First World War. The reality had been so different from what the civilian population had been told that it was ripped from history for a decade.

What will the Census Returns tell when they are made public? Any house over about a hundred years old will have a Census Return and the first return shows the people who first moved into the street. They are the pioneers who moved into the new houses. Census returns stay secret for a hundred years, so the details of Coppetts Road Estate will not be opened to the public until January 2032. They are not available at present.

However, there are older houses on the edge of the new estate. The Census returns of say Wilton Road, or Coldfall Avenue, could be very revealing. Who were these people who were moving into what was then a remote corner of London ? The two examples quoted below, one from Paddington and the other from Islington, are examples of the surprising patterns which may be revealed by this population movement.

The 1935 Ordnance Survey map showing the complete Coppetts Road Estate,

the newly built Coldfall School and the earlier houses in that part of Creighton Avenue.

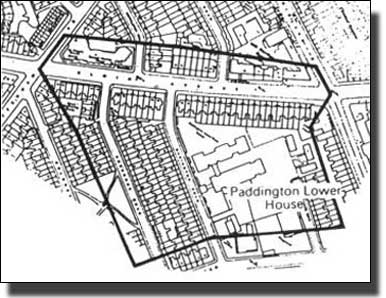

The Oakington Road Houses in the1881 Census

These maps and comments describe the 1881 Census which was taken a few years after these houses were first occupied.

Enumeration District No.25, 1881 |

Putting your mouse over the map will show part of the London Bomb Damage Map for this area. |

The 1881 Enumeration District with the list of roads enlarged for clarity

The country was divided into Enumeration (counting) Districts and each had an Enumerator who was responsible for distributing the census forms and helping the householders to fill them in where necessary. Then he collected the forms and added up the number of households, number in the family, ages, where they were born, etc.

These statistics were collected centrally so that the Local Government and Central Government could plan ahead. From our point of view today, the figures show how many people lived in these houses, their ages and where they came from.

Filling Up The Census, Punch

Where did Everyone Come From?

The Story of one Enumeration Distinct

Enumeration District No 25, 1881 (Kensington St Mary) includes a short length of Elgin Avenue and the end roads of the Neeld Estate. These householders were pioneers, gathered from many directions as the census returns show. There are 47 sheets of Census Returns with 1,175 persons listed. Of these, 194 (16.51 %) of the Heads of Houses were born in Wiltshire, or counties west of this, or in South Wales, and would probably have arrived in Paddington by the Great Western Railway.

The tendency in London was for people to want to move out towards the west, into the prevailing wind and away from the industrial smog of the East End and the Lee Valley. If there was work available, the newcomers would have preferred to stay there, rather than go east. And there was work, for the big shops of Kensington and Knightsbridge required large numbers of assistants and specialist workers to provide the goods and services which they offered. The census of Oakington Road shows dressmakers, a trunk buyer, a hosier's clerk, tailors, woollen drapers, warehousemen, silk buyers, a mantle cutter, upholsterers and other people who must have served in the prosperous new shopping centres of Kensington. The shops gave employment to a huge range of specialists, who would have been very polite, neatly dressed, not well paid but in fairly regular employment, and highly respectable. The area probably contrasted sharply with the unskilled and casually employed of parts of Lisson Grove, on the other side of the Edgware Road.

How the opening of the new Wheat Fields in

The USA affected Paddington

When the USA was spreading West and opening up the Great Plains for farming, they offered free land to anyone whe would work it. A flood of imigrants arrived, including many from Russia and Poland. These came with the clothes they stood up in and a sack of wheat as seed-corn. Ordinay European wheat could not stand the intense cold of the American West but this wheat had been bred over thousands of years to stand the harsh Russian winters and suited the Great Plains of the USA perfectly. As a result, from about 1850, the Wheat Belt in the USA spread rapidly northwrds. (The perfect novel for for older students about this period is My Antonia, by Willa Cather, a lyrical picture of the opening of the West by immigrants from the Russia and Eastern Europe and one of the best books she ever wrote.

As a result of this Russian grain, the World became glutted with wheat. British landowners had a always tried to keep the price of wheat high, but this ruined the English grain market. It was cheaper to import foreign wheat than to grow it here, so British agriculture collapsed. Thousands of agricultural labourers were thrown out of work and many fled to London to find work. Paddington and Marylebone attracted a high proportion of the new arrivals from the West Country. They arrived at Paddington on the Great Western Railway, found work in the new shops still being built there, and had no reason to penetrate further into London.

The 1881 Census shows that some who left Devon settled in Paddington. They got off the train and made new lives where they stood. Just as the East End of London housed the refugees from Russia and Poland; King's Cross attracted the Scots, and Euston/Camden Town housed the Irish, so Paddington seems to have attracted many of the migrants from the West Country brought by the Great Western Railway.

The first Oakington Road Census shows that of the 194 arrivals from the West Country, 52 (26.81%) were Heads of Households. Some wives and children 194 arrivals in the west. So were a surprising number of servants and lodgers who might in their turn, settle and bring up families.

The View From Devon

The other end of the story is told in 'Devon, part of the New Survey of England', 1954, published by David and Charles. The author, W.G.Hoskins, says:

| "My ancestors were men of no particular eminence even in local history, farmers nearly all of them until the collapse of local communities all over England in the early nineteenth century drove them off the land and into the towns and across the water to the Atlantic continent. But these were the sort of people who formed the foundations of any stable society.' |

These quotations from Hoskins seem relevant:-

‘Of the outward migrants in 1851, who amounted to thirteen per cent of those born in Devon, exactly half went to London.' 'Between 1861 and 1901 it has been calculated that 208 small parishes fell in numbers by anything up to sixty per cent.' 'Of those who left the county, most went to London, but in the eighteen seventies and eighties there developed a steady trickle overseas to the colonies and to the United States, helped to some extent by the cut-rates of the Atlantic shipping companies and by the railway rate-war on the other side.' |

He describes the flight from the country during the nineteenth century. That was the destruction of a country way of life which had lasted for centuries. Here, in Islington, is a town community being uprooted. What is their story? The 18 census returns can help in this.

One family in Oakington Road started by going to Canada where one child was born, to the United States for the birth of the second, and to Paddington for the birth of the third.

A scatter map showing where the first people in Oakington Road came from. People did not come only from the west. In Elgin Avenue there are people from France, perhaps refugees from the 1870 France Prussian War. If so, they were not the first to flee from France. Isambard Brunel fled from the French Revolution to New York where he became the Chief Engineer. Later he came to Britain and set up the block making machinery for the Navy, the first mass production line in the World. He introduced orthographic projection to Britain from France where it had been a state secret for thirty years. (++ See Graphic Communication, by Jack Whitehead, 1985).

In "The Growth of Marylebone & Paddington" I described the building of Oakington Road, Maida Vale, in 1868 and discovered details of the people who first moved into that newly built terrace.

The census also shows railwaymen, as one would expect so near Paddington Station.

Another Census Story, taken this time from Islington

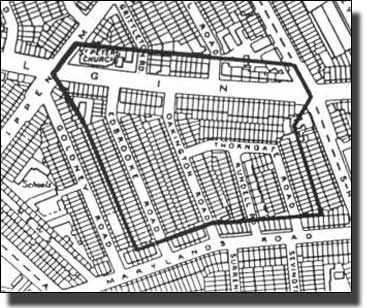

Here, in Islington, is a town community being uprooted. What is their story? The 1881 census returns can help in this. When Queen's Head Street School was being built in 1884, it was difficult to find a site in a busy, built up area and eventually it was decided to demolish a row of old houses as the site or the new school.

The 1870 O.S. map with the houses to be demolished coloured in.

This became the tiny site of Queens Head Street School

21-27 St Peter’s Street, Islington, built

1840

We have no picture of Queen's Head Street but this one of nearby St Thomas 's Street must have been similar.

The Queen's Head Street Census Returns

The 1881 Census reveals that 133 people of all ages lived in the 18 houses in Queen's Head Street. We do not know the numbers of the two houses in St Thomas 's Street so they have been ignored. In one house there were two old people in their seventies. Nearby was a rooming house with ten people in five separate households. Another house had two families with eight children between them, all of school age. No two houses were alike. Of the 133 people in the terrace, 36 were adult males, 44 adult females and 16 adolescents below the age of 21 and working. There were 25 school children and19 below school age.

Where did they come from? Three quarters of the people, had been born in London. Some Heads of Households had come from outside. Some had married London girls and had families. In contrast to the Paddington census, of the 33 who had been born outside London, only twelve had come from the West Country. Others had come from Birmingham, Kent and the Eastern Counties. This seems to have been a London community. Some may have already been driven out of the City of London by the intensive rebuilding between 1860 and 1880. If so, they were being moved on again.

The variety of their skills illustrates the wealth of small factories in the area. Clerkenwell and Islington, which were just outside the restricting powers of the City of London and their powerful guilds, gave shelter to a huge variety of small trades, some of them highly skilled. In this one short terrace were a locksmith with two apprentices, a cotton spinner, a ring case maker, cardboard box makers, a telegraph engineer, a gold chain maker employing his son and a boy, a watch jeweller, some carpenters, a wire twister, a steel spectacle maker, cabinet makers, an ivory turner and other unusual trades. Some, like the watch jeweller, will have done only one small part in the making of the final objects. Many may have worked at home, in a separate room or even on the kitchen table. The area was full of people who each did their part and passed on the batch each day, or each week, to the next specialist. It was a conveyor belt system dotted round neighbouring streets. Besides these craftsmen, there were laundresses, nurse maids, clerks and a bookmaker.

There were also three teachers, two of whom called themselves Board School Teachers, as if to stress that they were trained teachers and not just people who had drifted into Dame School work. This was eleven years since the School Boards were set up and began training teachers. Clearly the London Board was getting a reputation.

Using the Census in the Classroom

This can be a n interesting class activity.

- Print off forty or more consecutive sheets, so that each child can have one and there are some over for the faster ones. If the sheets are enlarged to A3 to make them easier to read and covered in plastic, they can bcome a permanent school resource.

- Decide what informaton can be obtained from the sheets, e.g.

- Number of the house

- Number of households in the house

- Anaysis of each houehold

- Head of House, male or female and age/where born

- Others in family

- Boys and their ages/where born/under school age/at school/at work/employment

- Girls and their ages/where born/ under school age/at school/at work/employment

If these categories are printed on a standard grid and each child has a copy, the ananysis of a complete row of houses can be completed in a double period and a picture of the pioneers in the street emerges and perhaps tells an interesting story of population movement at a particular period of time.

last revised: January 7, 2013