The Roundhouse from the Eighteen-sixties

By 1860s the Roundhouse had become a shed for corn and potatoes.1 In 1869 the building was leased to W. & A. Gilbey Ltd. as a bonded warehouse for wines and spirits. The railway tracks within the building were removed and a wooden gallery made of huge timbers added, to carry the vats of maturing whisky and brandy. A loading bay and two double doors were built on the Chalk Farm facade. The building continued as a secure bonded warehouse for nearly a hundred years, until Gilbey’s finally gave up its use in 1963.

By this time the building had been listed Grade II*. Therefore a new use had to be found for it without drastically altering its structure. The Roundhouse had survived only by chance. It was useless for its original purpose of turning engines (which had been moved to a completely different area) but its unusual shape and lack of windows had not prevented it from being an efficient bonded store. It was just luck that Gilbey’s happened to be on the spot and able to make use of a difficult building. Otherwise it might have been demolished years ago. Pure chance saved a noble building, simple, distinctive and exuding power, like a great dinosaur left stranded in a changed world.

The Roundhouse and Centre 42 in the Nineteen-sixties

When Gilbeys left Camden Town the Roundhouse became empty. The playwright, Arnold Wesker was fired by the idea of using it as a public space, open for any form of public entertainment. Theatre, dance, circus, all would perform there and people would pay what they could afford for entrance. In 1960 the Trades Union Congress passed Resolution 42 which declared that the building should become a centre for the arts, and this gave its name to the Wesker project. From then on it was called Centre 42.

In 1964, the lease of the Roundhouse still had sixteen years to run. When it was bought by Selincourt & Son, their managing director, Louis Mintz, gave it to Centre 42. The Roundhouse Trust was set up in 1965 with Arnold Wesker as artistic director and George Hoskins as administrator, but money was hard to raise.

Wesker had set his mind on a fully equipped theatre, with restaurants, film facilities including a dark room and cutting facilities, and ideal working conditions for the actors. All admirable and all expensive.

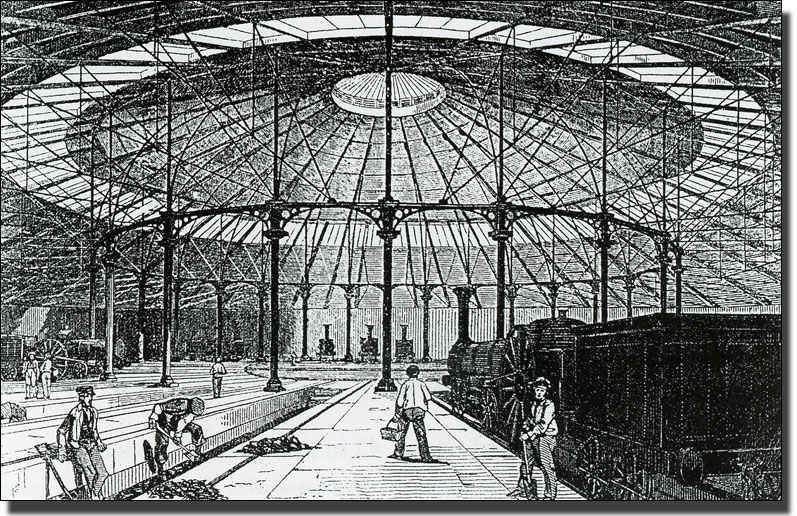

Converting the building into a theatre would always be difficult because of the central ring of cast iron pillars. The 1837 engraving on page 130 shows this perfectly. Remove the three nearest columns and you have a classical theatre shape. Leave them in place and the sight lines are blocked. Thus the fact that the building was listed, meant that it could never become a normal theatre. Secondly, the vast roof dispersed the sound. This was no problem for pop groups with their huge amplifiers, but made intimate dialogue difficult to hear.

The Roundhouse space was ideal for large, spectacular shows. Some highly acclaim-ed ones were staged and the unusual shape sometimes produced new invention. Peter Brook remembered that after putting on A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Stratford, a show which involved a great deal of gadgetry, they arrived at the Roundhouse with nothing - not even costumes. But the space so inspired the actors that they could forget all their lost sets and create a new, exuberant production on the bare boards. The audience sat on the floor while the actors performed around and among them.2

The 1837 engraving of the Roundhouse repeated to illustrate

the problem of the inner ring of pillars.

None of these

men

would have been able to see a stage at the other side

- In 1968, Peter Brook premiered his celebrated production of ‘The Tempest’. In the same year Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding, and The Doors all played to packed houses.

- In 1969, Tony Richardson produced his famous ‘Hamlet’ with Nichol Williamson, and Steve Berkoff his ‘Metamorphosis’ and ‘The Penal Colony’. Pink Floyd, Family, and Fairport Convention, played a benefit concert to help the funds.

- 1970 saw Jean-Louis Barrault’s production of ‘Rabelais’; ‘Godspell’; and P.J.Proby in ‘Catch My Soul’(the rock opera version of Otello written by Braeme Murray and Jack Good).

Wesker had always been concerned that bringing in outside productions would weaken his vision of the Roundhouse as an artistic centre with its own ethos and momentum. Instead it might become a mere theatrical space, let to outsiders. In 1972 he directed and staged his own play, ‘The Friends’, but so few tickets were sold that the backers wanted to close it after a fortnight. After six weeks they did so and instead brought in ‘O Calcutta’, the notorious sex show. This so outraged Wesker that he resigned.

George Hoskins then ran the theatre and put on some notable shows, including Arianne Mnouchkines’ famous Theatre du Soleil production of the play ‘1789: the story of the French Revolution’. This used the Roundhouse space in a flexible way. It shifted the acting areas from place to place, with several spaces in use at the same time, so that the audience had to move from one stage to the next, craning to find out what was happening, only to realize that they had become part of the action and they themselves were the crowd in the play. This production enjoyed great critical and popular success. People had a good time, but the shows were never financially secure.

In the spring of 1977, Hoskins had to step down due to ill health and Thelma Holt was asked to run the theatre for three months. With the Roundhouse burdened by ever increasing debts and its reputation as a centre of the drug culture, Thelma Holt determined to concentrate on using the building as a theatre. She stopped the rock concerts, which had become a mainstay of the building, and began to mount her own productions. When she was asked to take over as theatre director, she agreed to do so only if the Arts Council grant was increased. As a result, the subsidy rose from £30,000 to £47,500 in the following year.

The major problem was to tackle the acoustic and seating problems. To finance this Thelma Holt brought in prestigious productions, including Helen Mirren and Bob Hoskins in ‘The Duchess of Malfi’, Vanessa Redgrave in ‘The Lady from the Sea’, and Max Wall in ‘Waiting for Godot’.

Her own first and as it happened her last major production, was an elaborate staging of Bartholomew Fair, in which the whole of the Roundhouse became the fairground. Action took place before and after the actual performance. Genuine fairground equipment was borrowed from the collection at Wookey Hole, in Somerset; booths sold food and there were pens of animals, as if for sale. Peddlers walked among the crowd selling from their packs; there were puppet shows and jugglers, while Shakespeare himself walked among the crowd trying to persuade people to go to his show, which was being performed nearby, instead of this inferior Ben Johnson stuff.

The complication of this production tended to puzzle the audience. The play itself is complicated and rather diffuse, so that wrapping sideshows and animals around it as well, made the whole production bewildering. Academics who knew the play well, praised it. It added yet another dimension to the text and formed part of lectures they were to give for years, but it perplexed most of the audience. As a result, it was not a financial success.

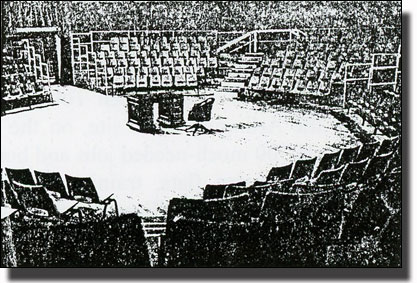

Thelma Holt then set about converting the Roundhouse into a theatre-in-the-round, on the lines of the Manchester Royal Exchange. Like the Roundhouse, this Victorian building had been cavernous and with bad acoustics. Accordingly, Richard Negri, the architect who had so successfully converted the Royal Exchange and D.K.Jones who had solved its sound problems, were invited to tackle the Roundhouse. Negri designed a central acting space with seating inside the columns, on the edges of the old turntable. This reduced the seats from 940 to 600. Lit from above and with a large canvas awning suspended over the central space, the theatre became more intimate, while the sound was contained, instead of disappearing into the roof space.

Auditorium designed by Richard Negri in 1977, similar to his Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester. The stage is set for Family Reunion, by T. S. Eliot. |

|

The Royal Exchange Theatre now had a London venue. The London and Manchester spaces were similar; scenery on this type of stage was minimal; so Manchester productions could be brought down easily. This was seen as a new form of touring. Manchester and theatres from abroad used the venue until 1983, when funding failed.

In 1981 Thelma Holt had persuaded the Greater London Council to subsidise the Roundhouse for £120,000 a year. This was not all she needed and economies had to be made. Thelma Holt had filled the building for six years from 1977, but inexplicably Camden and the Greater London Council refused further funding. They had the money but withheld it. The Arts Council would fund only if the local authority was prepared to match their contribution. When Camden Council refused to support the theatre, the Arts Council withdrew its subsidy and the Round-house had to close, with recriminations all round. All creditors were paid, but in 1983, after eighteen years, the theatre became dark.

Shortly afterwards the Council sunk the money in a Centre for Black Music and Drama but the enterprise collapsed in 1990.3

The Camden Goods Yard: Public or Private Housing?

Community Housing in Camden Town

At the same time as people searched for a new use for the Roundhouse, the battle about the future of the Goods Yard site continued. It was owned by the National Freight Corporation, which hoped to develop it for profit. This would be achieved by building expensive house for sale. In 1987 there was a five-week Inquiry into their plans to develop the fifteen acre site for private sale. Camden Council wanted instead to compulsorily purchase the site and develop it for fair-price rented accommodation. Should it be for sale or renting? What sort of people should be able to live there?

In December 1987 the Inspector ruled in NFC's favour. A new access road would have to be built from Ferdinand Road, under the rail line from Camden Road to Primrose Hill, at the cost of several million pounds. This would be paid for by the Ministry of Transport, so that figure did not come into the housing equation. Later the proposed demolition of an industrial building in Oval Road was turned down, so that the through road could not be built, but the plan for speculative private housing had won the day.

However, the slump put paid to that particular scheme almost at once. In 1990 Hyperion, the property arm of the National Freight Corporation, proposed a multi-million pound scheme to build 437 ‘yuppie type' homes on the site and a large office development. This plan did not include any community housing, leaving Camden with no planning gain at all. Supported by a vigorous local protest campaign, Camden opposed this.

At about the same time, the Council planned to reposition the Arlington Road Works Depot and the Jamestown Recycling Centre on the Goods Yard site. This would make room for low-rent housing development in Arlington Road, on the south side of the canal. In October 1990, Camden Town Development Trust, a charity, proposed new plans for the Arlington Road site. They proposed to create nearly 700 much-needed jobs and house 207 people on Camden 's waiting list by erecting 59 low-rise flats, training workshops and a creche. All this was to be subsidized by shops and offices, together with a cafe or restaurant built alongside the canal.

In the event, Community Housing Association developed the site. CHA, twenty-five years old in 1998, has been awarded no fewer than 11 design awards in the past few years. They have built in Castlehaven Road, Kentish Town, redeveloped the old North-West Polytechnic in Prince of Wales Road as housing, built on the former Bedford Music Hall, in Camden High Road, in Camden Gardens as we shall see, and in a dozen other places in Camden and surrounding boroughs.

Their policy is to work with the grain of existing local houses, fitting in sensitively with the neighbourhood and employing first class architects. As a result, the whole fabric of Camden Town and other areas has been upgraded in the last couple of decades. 4

Footnote