The Building of the Regent's Canal

Introduction

Paddington Canal, which seems so old to us, was in fact almost the last section of a much earlier and larger canal system. The rivers of the Midlands manufacturing towns had been linked by a series of canals to form the Grand Junction Canal. By the end of the 18th Century the canal had cut its way to the edge of London but London had already been expanded as far as Paddington and this was as far as the Canal could penetrate.

In 1800 the Canal reached Paddington by travelling along the 100 foot contour. Canal building depends on finding a route which falls slowly so that the water moves continually, but very, very slowly, or the water will drain away. A canal has to fall at only about 7 or 8 centimetres a mile, so canal building involves very delicate engineering and the canal has to twist and turn to follow the contour of the land. It cannot flow rapidly like a river.

Inevitably water would be lost so the canal company had to find rivers or build reservoirs, all along the route or their barges would often lie stranded, with no water.

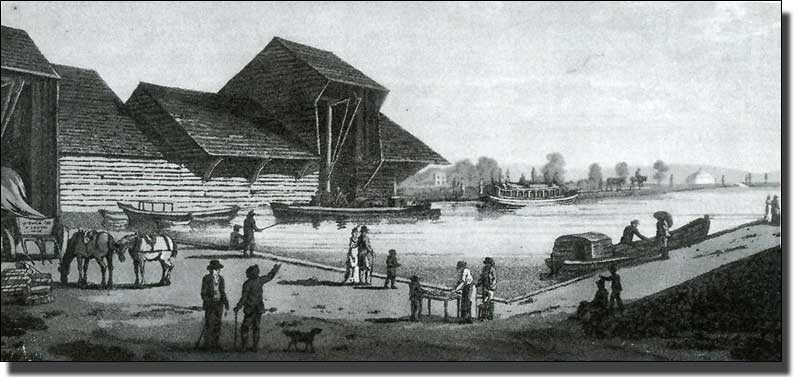

Paddington Basin in 1801, drawn by Henry Milbourne

and engraved by Joseph Jeake

Having reached as far as it could go the Paddington Basin was created in an open field, with a single loading building. This was a timber structure with a taller central section to house the crane and a large overhanging roof where barges could be unloaded under cover, but there was nothing else at first. Soon the Basin was surrounded by warehouses of all kinds. The only separation of use seems to have been that the piles of manure were confined to the further bank, near North Wharf Road.

At some time this timber building was replaced by a brick one with an over-hanging slate roof. This could still be seen at the Edgware Road end of the Basin until 1998, when I photographed it from the Metropole Hotel above.

Photograph of the Loading Building in 1998

++TRY TO MAKE A PHOTOGRAPH OF THE SAME SITE TODAY FROM THE SAME SITE IN THE METROPOLE HOTEL

The loading building was listed Grade II and mothballed to be used at the other end of the Basin as a Canal Boat Reception Building. In 2012 this has not happened and I do not know where the building is. I hope it has not slipped off the end of the contract, as seems to have happened with the Geological Garden we built on the Paddington Academy site. This was to be saved and re-erected but I cannot find out where it is.

To return to1800, the Grand Junction Canal Company was free to develop an area of 36 acres as it pleased. The Company developed the site as a trading estate with large warehouses and some modest cottages. In AD 2000, No. 35 North Wharf Road was one remaining example. Listed Grade II, it was demolished as part of the new development of that period.

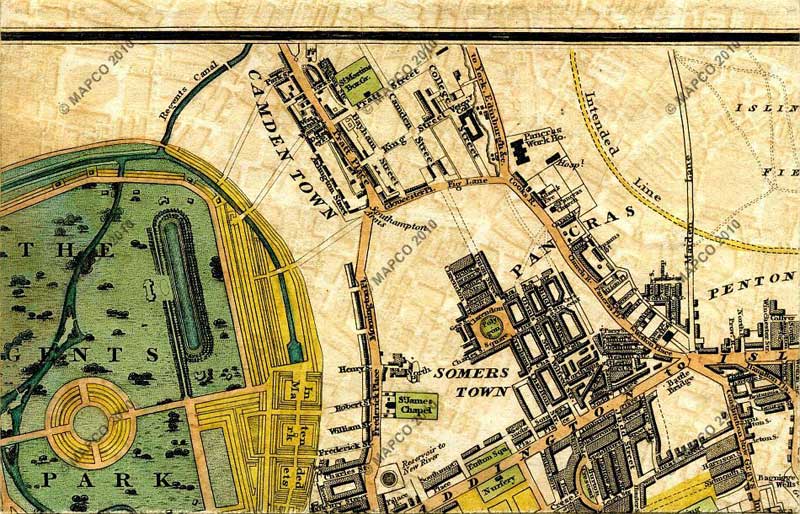

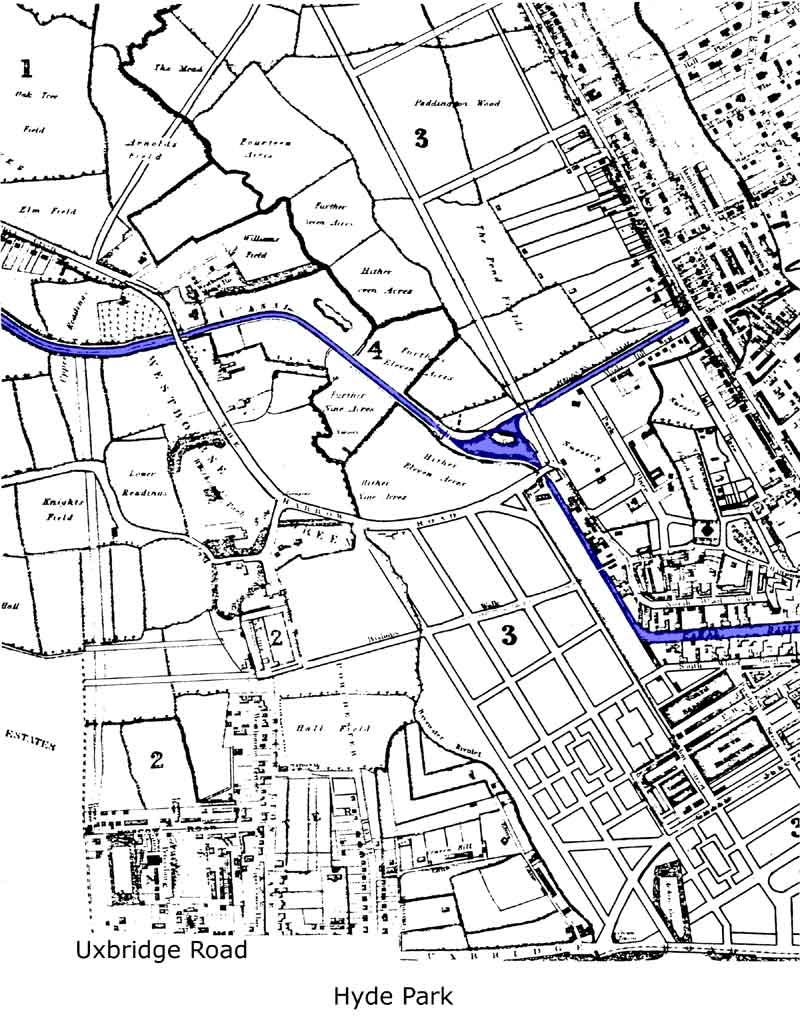

The Faden Map, 1810.

This seems to be the earliest map of the Paddington Basin apart from the sketched outline on the Bishop of London’s tithe map. We searched hard to find a map showing the Grand Junction Canal but not the Regents’s Canal, so finding this map was exciting, with the table in the archive room gradually becoming covered in maps, all too early or too late. Finally the Archivist produced this Faden map, still folded in its stiff paper pocket, almost as bright and new as when it was sold to some unknown coach owner five years before Waterloo.

Mac Faden was one of the many Scotsmen who came to London after James I succeeded to the throne and, like many others found it expedient to simplify his name as there was considerable antagonism to Scotsmen at that time. He became a very important mapmaker, involved with the Ordnance Survey.

The Canal begins to Transform Paddington

Canal trade developed rapidly. Goods came down from the Midlands to eager markets in London to be distributed from Paddington by horse and cart. Soon the area became congested with delivery wagons: the rural peace was gone and the polecats which used to terrorise the chicken runs were memories.

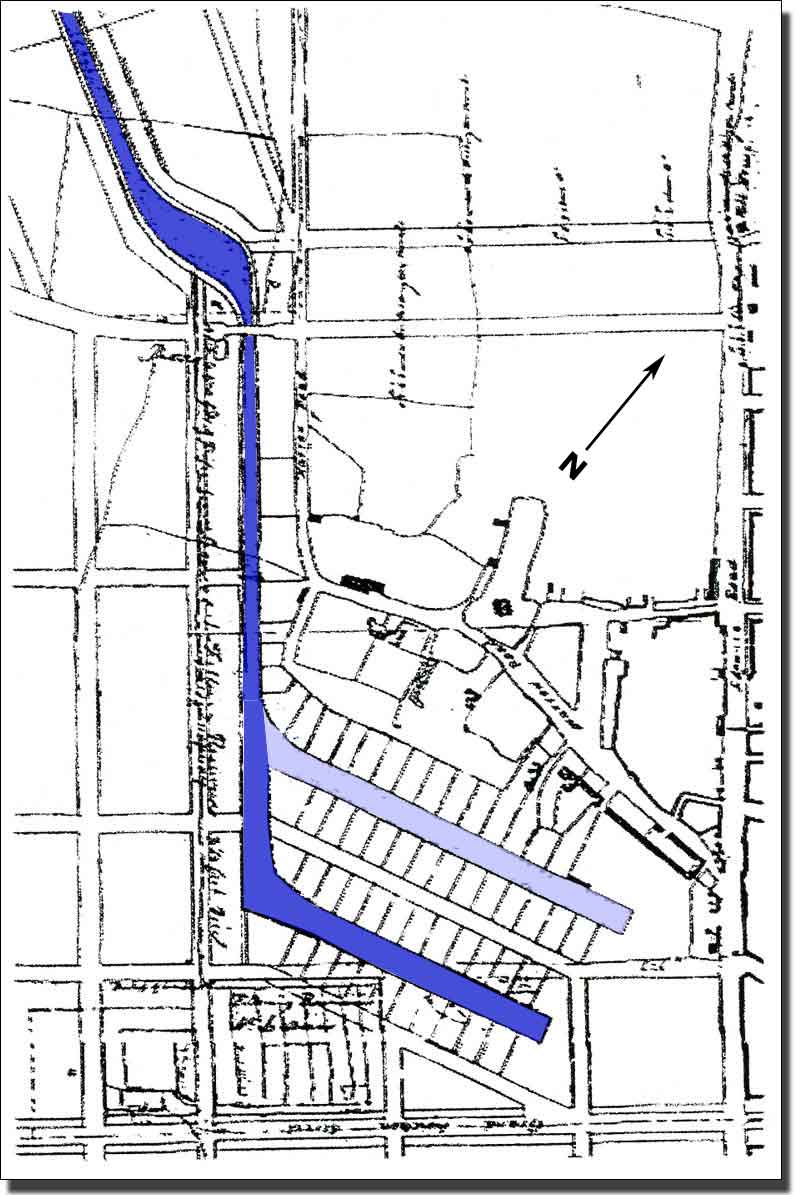

The War with France

Having reached Paddington, the whole canal system became more important to the country and not just to the Midlands. Britain had been at war with France for years. Napoleon's ships frequently raided our coastal shipping, sinking them, or stealing both ship and cargo. Goods were safer when travelling by inland canal than exposed to danger at sea. Helped by this, Paddington trade exploded. Indeed barge traffic increased so rapidly that a Second Basin was planned at Paddington, parallel to the first. The map below shows the proposed Second Basin on what is today Praed Street and the St Mary's Hospital site.

The planned Second Basin for Paddington.

I am grateful to Geoff Saul for pointing out this plan to me.

Some wharf owners were enthusiastic about the idea of a Second Basin, while others were more cautious and farseeing. Paddington might not retain its monopoly: might not remain the canal terminus for ever. The canal had reached Paddington so goods for Paddington and the West End could be carried economically by cart from the Basin to the West End of London. This was easy, but many of the goods were destined for overseas and had to be taken to the deep water docks at the Pool of London. Carrying them by cart all the way to London Docks was a very different matter. The unloading and transfer to lumbering carts for the rest of the journey was slow, expensive and would cause even more congestion in the narrow streets of London.

Some wharf owners were enthusiastic about the idea of a Second Basin, while others were more cautious and farseeing. Paddington might not retain its monopoly: might not remain the canal terminus for ever. The canal had reached Paddington so goods for Paddington and the West End could be carried economically by cart from the Basin to the West End of London. This was easy, but many of the goods were destined for overseas and had to be taken to the deep water docks at the Pool of London. Carrying them by cart all the way to London Docks was a very different matter. The unloading and transfer to lumbering carts for the rest of the journey was slow, expensive and would cause even more congestion in the narrow streets of London.

Very soon there was a demand to extend the canal to the Port of London and the deep-sea ships. Many were sure that a further canal to London Docks would be built sooner or later. Nobody realised how difficult and frustrating this would be. Politics, the end of the Napoleonic War, the biggest volcanic explosion in recorded history, mass starvation and the threat of food riots, were all to affect the progress of the Regent’s Canal and the problem of borrowing money to complete the project was a repeated worry.

Planning the Second Canal

A second canal, from Paddington to Whitechapel, was under discussion soon after 1800. Three or four proposals were made for a 'London Canal' and reached the Parliamentary Notice status. In 1802 the Chairman of the London Dock Company asked John Rennie to survey possible water sources for a canal from Paddington to Limehouse, but the Act of Parliament permitting the cutting of the Regent's Canal took some years to achieve.

A level route to Camden Town lay ahead and apparently everything would be simple s far as there. At Camden Town there would be a sudden change of levels and locks would be necessary, but until there the ground was level,

++MAKE A MEMORY MAP OF THE AREA NORTH OF LISSON GROVE TO SHOW THE CONTOURS AND PRIMROSE HILL ETC BEYOND.

++TURN THE MAP THROUGH 180 DEGREES AND MAKE A MEMORY MAP OF THE AREA NORTH CAMDEN TOWN LOOKING SOUTH TO SHOW TE CHANGE OF LEVELS

The Crown Properties object to the Proposed Route of the Canal

The Canal had reached London on the 100 foot contour and there was an almost level pathway to Camden Town ahead, but this crossed Marylebone Farm.

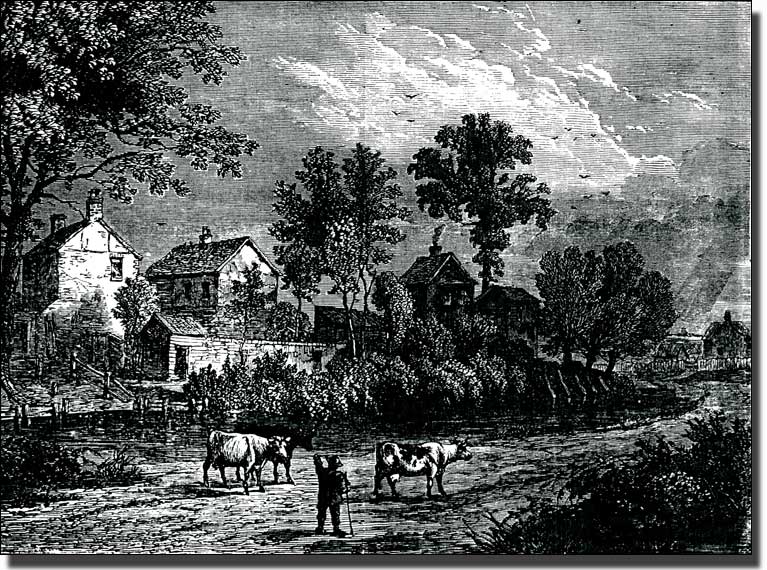

Marylebone Farm in 1750

Marylebone Farm in 1750

This was Marylebone Farm in 1750 and little had changed since then , but it was Crown Property and in 1811, only nine year’s time, the lease was due to fall in. The whole farm would become the property of the Crown once again and there were plans for a major development in the area. John Nash had been commissioned to build an exclusive and expensive estate on the site. This was to become the fashionable centre of London, directly linked to Parliament by a new Regent Street. Nash was not willing to tolerate dirty coal barges spoiling his newly painted stucco buildings.

After long negotiations he agreed that the Canal could pass round the north side of Regent’s Park in a cutting. It would be out of sight and form a deep ha ha to protect his estate from easy access by the general public. He forced the canal to take a much more expensive route round the north of his new estate. The Canal Company was forced to cut tunnels, excavate a long, deep cutting round the Zoo and build bridges all the way along to Camden Town. It did not cost Nash anything but it forced the Canal Company to appeal for more and more money. By 1811 work started far higher up Edgware Road than the Company had planned.

++MAKE A MEMORY MAP OF THE CANAL ROUTE LOOKING ALONG THE CANAL TOWARDS EDGWARE ROAD. This should show Edgware road rising up and explain the need for a tunnel.

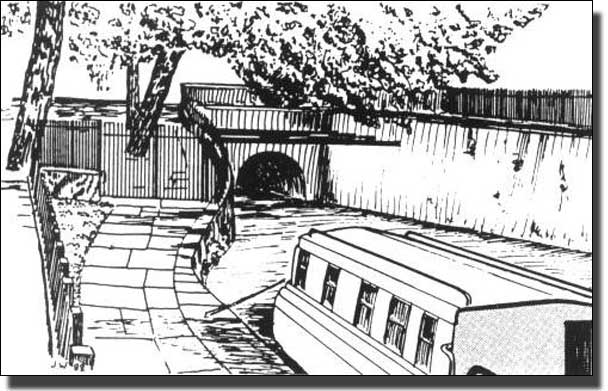

Forcing the canal up Maida Hill caused problems to the Company. Edgware Road was above the canal level and canals cannot rise without locks, so the canal had to tunnel under Edgware Road in a shallow tunnel, much lower than usual. There was not enough height for a towpath and a horse to draw the barges through this tunnel. Instead a very low tunnel was cut under the road and a different way to get the barges through was devised. At the entrance to the tunnel the horse was detached and led across Edgware Road. The barge was then driven through the tunnel by a special gang of men who used to lie on their backs and ‘leg’ the boats through by walking along the roof of the tunnel. On the other side of Edgware Road, the horse was reattached to the barge and drew it along the towpath as before and the ‘leggers’ waited for the next barge to arrive.

It was not until 1812, when Nash had changed the route, made it much more expensive to achieve, and renamed it as it the Regent's Canal, that the proposed canal route began to appear on maps.

As a result of all this delay, it was nine years from the time the canal was first suggested before the map of the new Regent’s Canal began to appear.

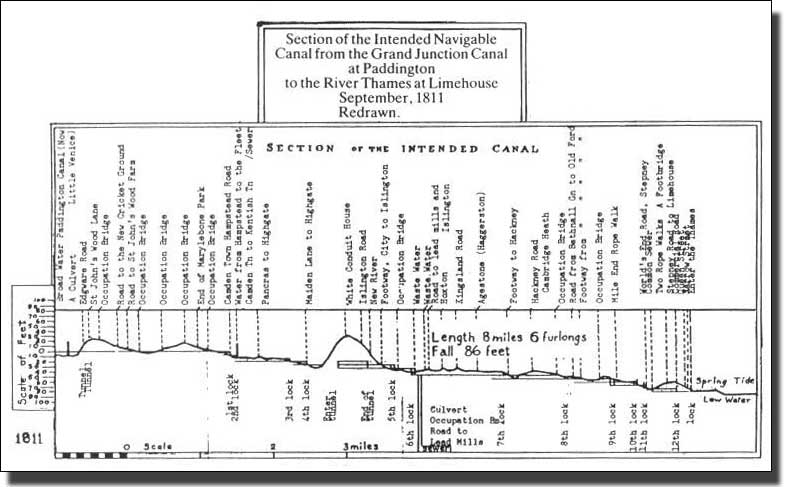

The Plan of the Regent's Canal from Paddington to the Thames at Limehouse.

Section of the Regent's Canal

This section of the route shows the way the water would fall on its way from Paddington to the sea level at the Pool of London, which was 100 feet lower. The vertical scale has been greatly enlarged of course. The real slope of the water is only 5 inches (12.5 cms) a mile. This would be completely impossible to show at the correct scale.

The first tunnel, under Maida Hill is on the left and the deep cutting which skirts Regent’s Park and the Zoo is shown as Occupation Ridge. Landseer lived at Punker’s Barn, a high point above the tunnel, and George Elliot lived in the Eyre Estate which overlooked the cutting beyond. At Camden Town the Company had to build the first locks since Slough. Then the canal had to tunnel through the Boyne Hill Gravel ridge in Islington, and further locks were needed beyond that to descent to sea level.

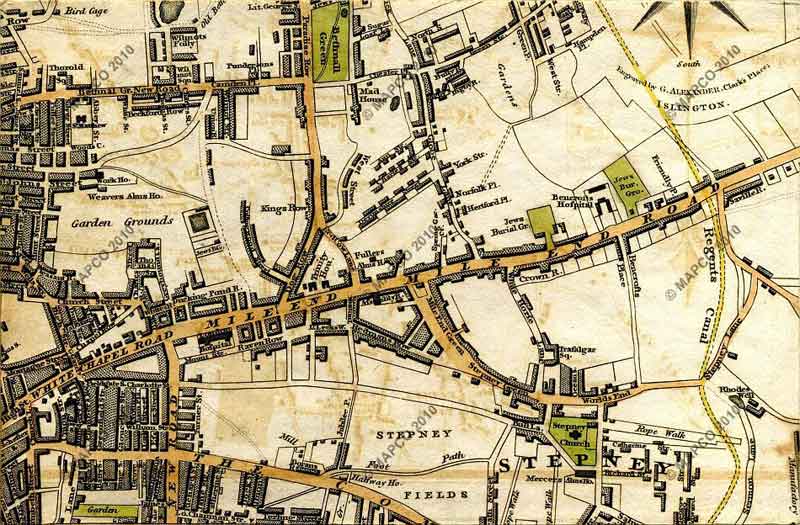

Darton's Map ol London, 1817

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

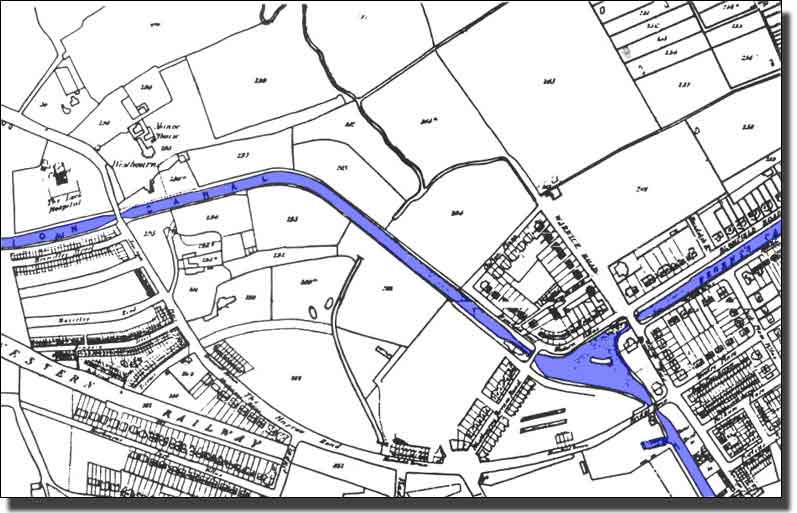

This splendid coloured map by Darton, 1817, appeared during the actual building of the Regent’s Canal and panels from it are reproduced here to trace its tortuous route and unending difficulties, physical, historical, volcanic and financial. It was an epic journey, battling against all odds. It took just about as long as it took Odysseus to reach Ithaca from Troy to and the gods were equally unforgiving.

Remove? It was nine years from the time the canal was first suggested before work could be started. In 1811 the leases of Marylebone Farm, which was Crown property, were due to fall in and John Nash had been commissioned to build an exclusive and expensive estate on the site. He objected to dirty coal barges passing through his freshly painted stucco estate. On the other hand, it could pass round the north side of Regent's Park in s deep cutting. It would be out of sight and form a deep ha ha to protect his estate from the general public. He had the canal diverted it into a much more expensive route north of his new estate. The Canal Company was forced to cut tunnels, excavate a long, deep cutting round the Zoo and build bridges all the way along to Camden Town. It did not cost Nash anything but it forced the Canal Company had to appeal for more and more money. By 1811 work started far higher up Edgware Road than the Company had wanted. |

This map and others are reproduced here by kind permission of Mapco, a splendid source of early London maps.

The course of the Regent’s Canal which had not been built by the time this map was surveyed,

is marked on this map in Yellow as it was still an ‘improvement’ at the time.

The splendid 1817 Darton map was produced during the course of the building, so various panels from this map have been reproduced to illustrate the route and list the many problems encountered on the way.

|

|

|||||||

The route of the New Canal

++I have given up the idea of imposing the contour lines on the map in favour of a Memory Map showing the contours in 3D.

Old version The Company hoped to cut their canal parallel to the New Road (now called Marylebone Road ) but Regent's Park was in the way. The lease of Regent's Park Farm was to come to an end in 1811. It was Crown Land and John Nash had been commissioned to build a long processional road from the Houses of Parliament along Regent's Street and Portland Place to a fine new estate of stucco houses in Regent's Park. This was to be the fashionable centre of London and Nash did not want a lot of dirty coal barges soiling his newly painted stucco. In the end he allowed the canal to run in a deep cutting around the edge of Regent's Park, where it would be hidden. At the same time the canal cutting act as a guarding moat which to keep the rabble out. To do this the Canal Company had to move its route further up Edgware Road, cut a tunnel under Maida Hill and a deep cutting by the Zoo and build numerous bridges to span the valley. It all cost a lot of money and at a very difficult time for raising money. In 1811 the Regent's Canal Company could begin work on their canal. At first it was level digging and Little Venice was formed when the new canal branch towards Camden Town was cut and ran for a short distance to Edgware Road. There a tunnel was cut under the road but it was too small for a towing path. The horses had to be detached and the boats were driven through by men who laid on their backs and ‘legged' the boats through by walking along the roof of the tunnel. |

The first stage of the Regent’s Canal was from Paddington to Camden Town. At Camden Town there is a sharp drop in the land levels so locks would be necessary, but as far as there it was level ground. The Company hoped to cut their canal along level ground parallel to the New Road (now called Marylebone Road) and then to veer across to Camden Town, still on level ground. Unfortunately Marylebone Farm was in the way. This was to become a complete barrier.

In 1811, when the Maida Farm lease had fallen in and negotiations were completed, the Regent’s Canal Company could begin work on the canal. At first it was level digging from the Junction Canal. Little Venice was formed when the new canal branch towards Camden Town was cut and ran for a short distance to Edgware Road.

Maida Hill Tunnel, 250 metres (270 yards) long

Western Tunnel Mouth looking east. There isn't a tow path inside

the tunnel so the narrow boats had to be "legged" through.

Click on this link to open a new window/tab showing the tunnel mouth on Google Maps

|

|||

| Bartlett and Britton, 1834 | Whole Map | Full Size | Full Size Map in New Window |

| Ordinace Survey , 1864 | Whole Map | Full Size | Full Size Map in New Window |

This map showing the path of the Regent’s Canal fourteen years after the canal had been completed. Little Venice had been formed but there were no houses near it.

The 1848 Lucas map showing Little Venice and

the first houses built on the high ground above the basin.

By 1848 houses had been built on the high ground overlooking Little Venice where they would have unrestricted views. There were houses too along Blomfield Road and the area become very fashionable.

The World Picture while the Regent's Canal was being built.

In 1812 Napoleon invaded Russia with half a million men. One of his excuses for attacking Poland on the way, was that the Poles were trading with England and breaking the trade embargo which Napoleon had tried to impose on Britain. There seemed no reason why, with that massive force at his disposal, Napoleon should not succeed. People were not thinking about investing in canals at that moment and the Regent’s canal Company had difficulty in raising money.

Napoleon’ Russian campaign was a disaster. The Russian army retreated and retreated, drawing Napoleon further and further into the country. Napoleon reached Moscow, only to find it burning. He hung about for a few weeks, the winter snows came early and Napoleon, unprepared for the Russian winter, had to retreat. The whole campaign was a dress rehearsal for Hitler’s failed attempt to defeat Russia centuries later.

The Explosion of the Tambora Volcano in April 1815

The Tambora volcano in Indonesia erupted on April 5th 1815, with the largest eruption on April 10th and 11th. Tambora was 14,107 feet high and is located on the Sumbawa Island of Indonesia. The volcano chamber, with its accumulation of magma built up over centuries, was emptied of its contents. The ash and gases caused substantial climate change, lowering global temperatures by one degree. The overcast sky, full of ash particles, deflected the heat of the sun and for two years there no summer. The volcanic rain, the meteosunami and climate change, killed livestock and destroyed crops. More than 92,000 people died as a result of the explosion itself and maybe 100,000 more perished from starvation. Tambora had 100 times the power of the Vesuvius eruption of 79 AD which was recorded by Pliny and was the most deadly eruption in recorded history.

Scientists have calculated that Tambora has erupted three times in the past 10,000 years. The 1815 eruption of the Tambora volcano is one of four eruptions to have been assigned a Volcanic Explosivity Index of 7. Thus the Tambora eruption was the most powerful eruption in recorded history. The immediate effect was to redden the sky but nobody had any idea at first of why this had happened and what it portended.

The Battle of Waterloo

By 1815 Napoleon had returned from Russia and gathered another great army. He was challenged at the Battle of Waterloo (near Waterloo in present-day Belgium,) on Sunday, 18 June 1815, about two months after Tambori had erupted.

In earlier times, when celestial events and battles remembered by only oral history, the soothsayers and historians might have linked the two events and recorded the red sky as a message from the gods. In 1815 the two huge armies had more immediate concerns. History was recorded by oral tradition, carried in the memories of old men. Napoleon and Wellington were confronting each other for the last time and were not interested in a mere reddening of the sky. Napoleon was defeated and the news from the battlefield was carried by carrier pigeon. A mere red haze in the sky had no mention, but both Waterloo and Tambori were to have a serious effect on the building of the Regent’s Canal.

Closing the War Factories

The end of the Napoleonic Wars caused the British Government to cancel all war orders immediately. For decades British factories had made boots, uniforms, armaments and a thousand other things for the Army and Navy. Suddenly all this stopped and masses of people were unemployed overnight. There was no unemployment insurance at that time. Local Vestries (local villages and town authorities based on the church parishes) were responsible for people who had been born within their own borders. Anyone who had moved into an area later, even if they had worked there for years, had to go back to where they were born to ask for help. Imagine this situation with hundreds of people on the move at the end of a war, or displaced by factory closures. It must have been a nightmare.

Foreign corn had become cheaper than home grown corn and threatened to undercut it. During 1813, a House of Commons Committee had recommended excluding foreign-grown corn until the price of corn grown domestically increased to £4 (worth £202.25 in 2010) per quarter (1 quarter = 480 lb / 218.8 kg). The political economist Thomas Malthus believed this to be a fair price, and that it would be dangerous for Britain to rely on imported corn as lower prices would reduce labourers' wages, and manufacturers would lose out due to the decrease of purchasing power of landlords and farmers. However, David Ricardo believed in free trade so Britain could use its capital and population to its comparative advantage Then there would be considerable increase of free trade. This debate would continue for years ahead. In 1815 prices were rising and people had no work.

With the end of the war and the prospect of peace with France, corn prices decreased and landowners faced falling incomes. In1815 the Tory government of Lord Liverpool passed the Corn Importation Act. This was designed to keep the price of corn high and so protect cereal producers in the Great Britain and Ireland against competition from less expensive foreign imports. The Corn Laws enhanced the profits and political power associated with land ownership. The fight against them was to become a thirty year campaign until 1846, when they were abolished, but this would be years ahead.

In 1915 the landowners wanted corn prices to be high at the same time as thousands were about to be thrown out of work. By 1816, the effects of the Tambori eruption also began to affect everyone. Food prices rocketed and overwhelmed the local Vestry charity funds. These had been designed to give old ladies ‘beyond their labour’ some coal and a few loaves of bread, not for mass unemployment in a slump. The immediate result of the high corn prices resulted in serious food riots in London.

The Regent’s Canal Company had run out of money yet again and work on the canal had faltered. The government was faced with food riots and at last, in 1817, it made an emergency loan to the Regent’s Canal Company to help it complete the canal and help get people to work. There was no real interest in the canal but the political unrest had stirred the government into some action. The loan helped provide work and slowly, very slowly, conditions improved.

The Route of the Regent’s Canal around built-up London

|

|||||||

Building the Bridges.

These bridges and the deep cutting, which Nash forced the Canal Company to build, added greatly to the Company debts.

++M PRIMROSE HILL TP

Camden Lock

++MAKE MAP OF CAMDEN LOCK 1 AND CAMDEN LOCK 2, TO SHOW AREA FROM PRIMROSE HILL TO INCLUDE ALL OF CAMDEN TOWN

|

||

| Whole Map | Full Size | Full Size Map in New Window |

Cross 1850 map

This piece of the Cross 1850 map shows the Battle Bridge Basin near King's Cross

It was built near York Way as the Canal Company anticipated a great deal of trade from here. Today it is the site of the Canal Museum.

|

||

| Whole Map | Full Size | Full Size Map in New Window |

|

||

| Whole Map | Full Size | Full Size Map in New Window |

This Basin was built early and carried a great deal of trade until after the Second World War.. It extended under a road bridge to the other side of City Road. Today the southern end has been filled in and is full of office and factory buildings. The northern end of the Basin is a peaceful backwater, lined with blocks of flats.and pedestrian walks.

|

||

| Whole Map | Full Size | Full Size Map in New Window |

At this time the area was almost free of houses so there was room for the canal to circle the existing town

|

||

| Whole Map | Full Size | Full Size Map in New Window |

|

||

| Whole Map | Full Size | Full Size Map in New Window |

++PRINT Smith's 1830 map London Regent's Basin here (which?)

The entrance to the Regent's Canal at Limehouse in 1823

By courtey of Wikipedia.

++REVISE THE FOLLOWING WHEN THE REST HAS BEEN COMPLTED

As with many Nash projects, the detailed design was passed to one of his assistants, in this case James Morgan, who was appointed chief engineer of the canal company. Work began on 14 October 1812. The first section from Paddington to Camden Town, opened in 1816 and included a 251-metre (274 yd) long tunnel under Maida Hill east of an area now known as 'Little Venice', and a much shorter tunnel, just 48 metres (52 yd) long, under Lisson Grove. The Camden to Limehouse section, including the 886-metre (969 yd) long Islington tunnel and the Regent's Canal Dock (used to transfer cargo from sea-faring vessels to canal barges – today known as Limehouse Basin), opened four years later on 1 August 1820. Various intermediate basins were also constructed (e.g.: Cumberland Basin to the east of Regent's Park, Battlebridge Basin (close to King's Cross, London) and City Road Basin). Many other basins such as Wenlock Basin, Kingsland Basin, St. Pancras Stone and Coal Basin, and one in front of the Great Northern Railway's Granary were also built, and some of these survive.

The City Road Basin, the nearest to the City of London, soon eclipsed the Paddington Basin in the amount of goods carried, principally coal and building materials. These were goods that were being shipped locally, in contrast to the canal's original purpose of transshipping imports to the Midlands. The opening of the London and Birmingham Railway in 1838 actually increased the tonnage of coal carried by the canal. However, by the early twentieth century, with the Midland trade lost to the railways, and more deliveries made by road, the canal had fallen into a long decline.

Then do a panel by panel account of progress and problems using 1817 Darton

The Railway Challenge

1 Maps showin First Camden Town Railway site

2 East India Railway (North London Line.).