The Arrival of the Grand Junction Canal at Paddington

The Regent’s Canal, which seems so old to us, was in fact the very last section of a much earlier and larger canal development. The rivers of the Midlands manufacturing towns had been linked by a series of canals to form the Grand Junction Canal. By 1804, when Tompson drew this map, it had already reached Paddington, connecting the industries of the Midlands to London. Bulk goods could now be brought easily and cheaply to the very edge of London.

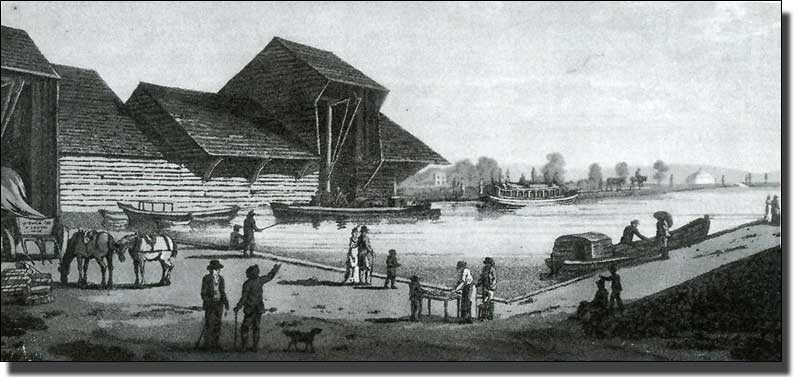

A large Canal Basin had been created in an open field at Paddington, with a single loading building. It was a timber structure with a taller central section to house the crane and a large over-hanging roof where barges could be loaded under cover, but at first there was nothing else. At some time this timber building was replaced by a brick one with a slate overhanging roof. This second building could still be seen at the Edgware Road end of the Basin until 1998. It was hemmed in by warehouses, now demolished, but the Metropole Hotel still towers immediately above. The loading building, which is shown in a photograph at the end of the book, is now listed Grade II. It was dismantled and mothballed for later use as a Canal Boat Reception Building at the other end of the redesigned Paddington Basin. By 2011, when the Paddington Basin has been largely redeveloped, this has not happened and I do not know where the building is. I hope it has not slipped off the other end of the contract.

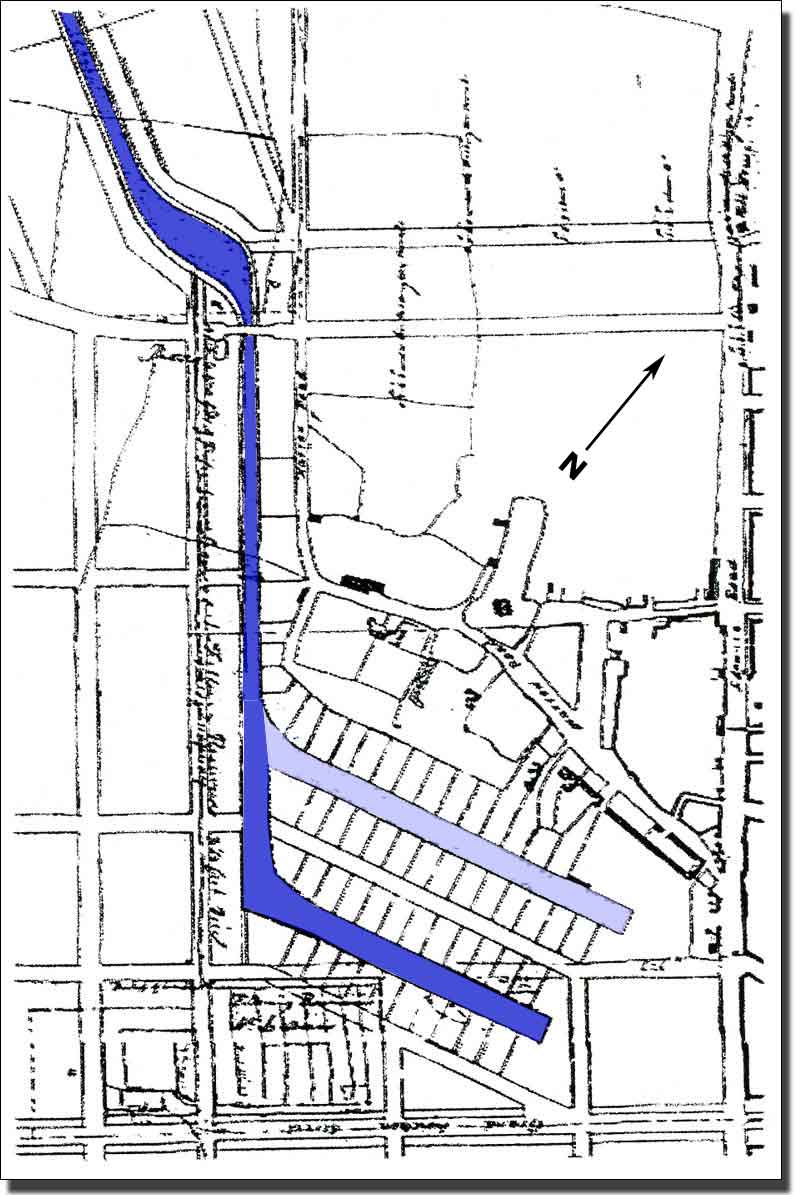

The Grand Junction Canal and Paddington Basin before the Regent's Canal was built and Little Venice was formed. The map shows the planned second Canal Basin. It was never built. |

|

Paddington suddenly became the terminus for goods and passengers from all over the Midlands. Road transport was so slow and expensive that frequently the quickest and cheapest way to travel even for passengers was by canal barge, while goods and minerals moved far faster than by road. By using four horses and travelling at a trot, Pickford’s could take a barge from London to Birmingham in two and a half days. Large furniture depositories arose around the Paddington Basin. Wharves held piles of building materials, coal, hay, pottery and for the return journey, manure for the fields and household rubbish to fuel brickyard kilns. While Camden Town still slept in her fields, Paddington was becoming an industrial centre. Indeed Paddington was so self-confident that a second canal basin was planned on what is now the St Mary’s Hospital site in Praed Street, Paddington.

However, most firms wanted their goods carried beyond Paddington, to the centre of London and especially to the docks, yet all goods arriving at Paddington had to be carried from there expensively by cart. Very soon there was a demand for the canal to be extended to the Port of London and the deep-sea ships. Soon there was a plan to build the Regent’s Canal to link Paddington to the open sea.

|

||

| Whole Map | Full Size | Full Size Map in New Window |

The Faden Map, 1810.

Faden’s map of 1810 is the only one I know which shows the canal system terminating at Paddington. Thereafter the Regent’s Canal was always shown on maps because by 1811 the idea of a canal from Paddington to Wapping had been forced through. Bills had been put through Parliament and soon the surveyors were tramping the fields.

|

||

| Whole Map | Full Size | Full Size Map in New Window |

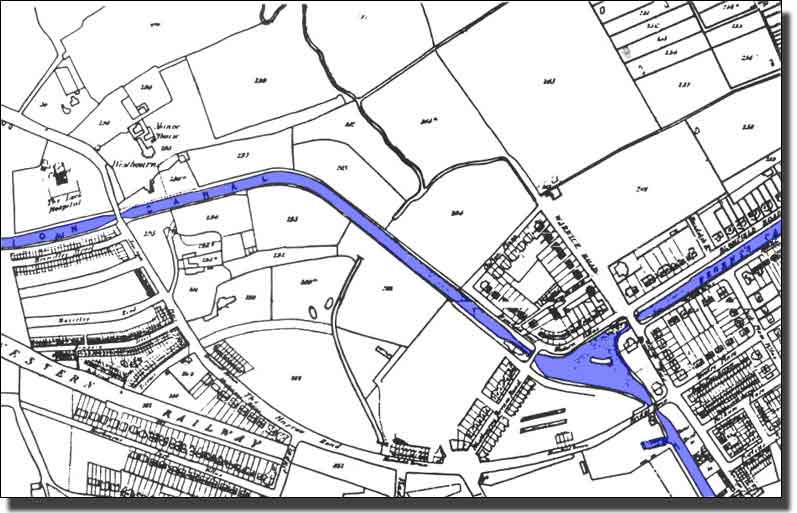

Bartlett and Britton's map of 1834, showing Regent's Canal and Little Venice

The 1848 Lucas map showing Little Venice and

The 1848 Lucas map showing Little Venice and

the first houses built on the high ground above the basin.

The Regent’s Canal Company

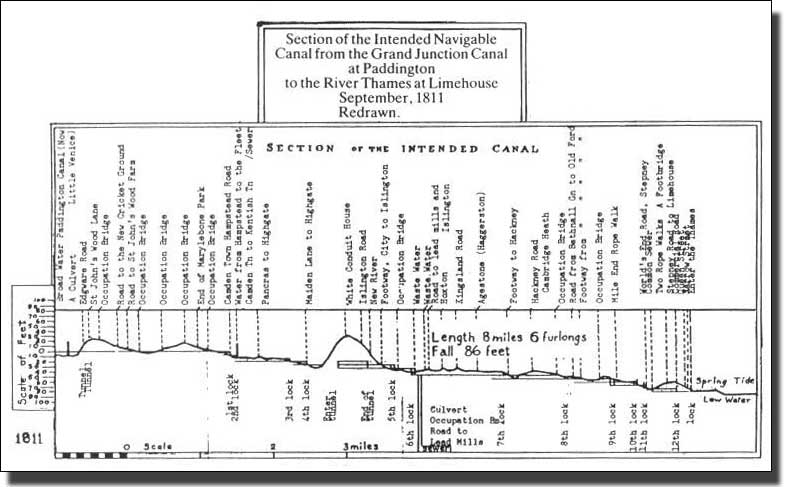

The map shows the route of the Regent’s Canal, while the section reveals some of the problems faced by the engineers. The canal company had to tunnel under Maida Hill and again at Islington, create locks at Camden Town and elsewhere, and negotiate with reluctant landowners. Nothing was to be easy, or cheap.

Paddington wharf owners and contractors, Paddington Vestry and all those profiting by the success of Paddington as the canal terminus, protested at the idea of the Regent’s Canal being built, as it would drain away their livelihoods. Other people were concerned at the loss of open space in Marylebone Farm (now Regent’s Park). This was public land and would be covered with private houses, becoming the preserve of the rich. Still others feared that the Prince Regent, who was promoting the development of this Crown land, would squander money on grandiose building, as he had squandered money before, and leave Parliament to settle the bills.

The Grand Junction Canal Company had brought the canal to Paddington along the 100 foot contour (30 metres) sweeping round the lower slopes of Maida Hill into Paddington Basin. To continue,Towards Camden Town they wished to stay at the same level, or fall lower. It would have been simplest to have continued under Edgware Road and through Marylebone Farm, but this was very valuable property indeed.

Nash was just starting to create Regent’s Park on the old Marylebone Farm. He did not want a canal to separate his new estate from Regent’s Street and his wealthy clients in the West End. He was creating an enclosed estate, cut off from the working world, difficult to enter except from Portland Place and a few chosen gateways. On the other hand, Nash liked the idea of the canal bordering his Park on the north in a well-wooded valley, insulating it silently and romantically from the outside world. The effect of that policy and its influence on public debate, on the separation of classes and the positioning of areas of public and private housing, we shall see continuing into the 1980s and beyond.

Denied the easy route along the Marylebone Road, the Canal Company had to tunnel under Maida Hill and skirt the newly developing Regents’s Park in a deep, expensive cutting. By forcing them to take such a long, circuitous route, he made the shareholders spend far more money than they had planned.The route involved many bridges. Where possible the canal was narrowed to only one barge width, allowing a shorter, cheaper bridge, but on the Regent’s Park stretch where the long bridges had to fly high above to span the wide cutting, so there was no advantage in narrowing the canal.

Section of the Intended Canal

The section shows the path of the Regent’s Canal straightened out. The distance from Broad Water, now called Little Venice, to the River Thames at Limehouse, is about six and a half miles as the crow flies, but the canal winds for nearly nine. It falls 86 feet as it passes through two tunnels and thirteen locks. There had been no locks all the way from Uxbridge to Paddington, and the Regent’s Canal was able to continue on this level course as far as Camden, Here there was a sharp fall in ground level which made locks necessary.

Section of the Regent's Canal

This was as it was originally intended in 1811, but not exactly as it was built.

The Locks at Camden Town

Saving water was very important. An average lock on the Grand Junction Canal holds 50,000 gallons of water, lost each time a boat passes through. Water from the higher reach flows down to the lower level and fresh water has to be provided from somewhere to replace it. The Welsh Harp, for example, like many other apparently natural stretches of water, is nothing less than a reservoir built to top up the canal. There is no Welsh Harp on the first Ordnance Survey map.

On 14 October 1812 work began on experimental locks at Camden Town, designed by Sir William Congreve (the inventor, not the dramatist). These were ‘hydrostatick locks ’, planned to save water. Two large water-tight steel boxes (or caissons) were connected by chains and pulleys. These failed at a cost of £12.000 and had to be replaced in 1814 at yet more expense. Instead, the Company installed double locks with an inter-connecting paddle, a system which saved nearly half a lock of water each operation. By 1816 the canal had reached Camden Town and opened a branch (now filled in) to Cumberland Market, but troubles persisted.

When the canal reached Agar Town, near King’s Cross, there was a pitched battle with pick-axe handles between canal navvies and the workmen employed by Agar. He was the grasping lawyer-landlord who had built Agar Town as a speculative venture, and now saw yet another way of making money. He sued the Canal Company for trespass, won £1,500, holding up work for several months. Then Thomas Hosmer, the Treasurer and one of those who first proposed the canal, ran off with the Company’s funds, was caught and transported. There was still no through route to the Thames and until there was, the canal could not hope to make a profit. The board had to raise still more money, but they also faced another problem.

The Water Companies had opposed the canal vigorously from the start. Hampstead Water Company had two sets of ponds on Hampstead Heath and a pumping station in East Heath Road. From the Lower Pond in East Heath Road ran a line of pipes supplying water to Fleet Road, Camden Town and along Hampstead Road to a reservoir at what is now Tolmer’s Square. A similar pipe ran from the Highgate ponds to supply Kentish Town. Further along the proposed canal route, Rennie, of the New River Company, which had no fewer than sixty pipes radiating from New River Head, opposed the cutting of the canal vociferously.1

At that time water pipes were mere elm tree trunks, bored out, joined end to end and laid only a hand’s below the surface, so a canal several feet deep would destroy the pipes. As the water flowed by gravity, the pipes could not be raised or lowered without much leaking. At this period water could not be carried to the upper floors of houses because of lack of pressure, so raising or lowering the pipe would not have helped. Nor would pumping have solved the problem as the water would have sprayed out at every joint. Eventually the Canal was forced through by Act of Parliament and from that time on the Hampstead Water Company supplied water to the district north of the Canal only.

All this controversy cost the Canal Company the litigation, delay and money. In the end it was only mass unemployment and the threat of violent public disorder that finally got the job done. By 1817 the country was in a post-war slump because, with the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, in 1815, all war work had stopped. Supply contracts were terminated overnight. For example, Isambard Brunel, father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who built the Great Western Railway, had built a factory to mass-produce army boots and was left with nobody to buy them. Other manufacturers were in a similar plight. There was no work for the returning soldiers, who became vagrants and a heavy weight on their local parishes. In Paddington, a hundred years earlier, after another war, the church wardens recorded, ‘Two shillings paid for bread and cheese to 24 poor sailors on their travels’. Anything to get them out of your parish and pass on the responsibility to someone else. The provision for destitute people had not changed in the following century, so local parishes were feeling the strain.

It was in this atmosphere of rising economic stress that the Poor Employment Act of 1817 was passed and the government agreed to lend the Regent’s Canal Company £200,000 to complete the canal. A century later, similar agitation at the end of yet another long war, brought about the Russian Revolution. It is true that in 1817 the British government was more concerned to create work and so buy peace for itself than to complete the Canal, but it served to finish the project.

By 1820 the Canal was finally open. At last Midlands manufacture could be carried smoothly to the waiting ships in the London Docks and from there to the whole world. Even so, the Canal was never to be a financial success because it was swamped by its accumulated debts. Earlier canals had made a lot of money, but the Regent’s Canal arrived too late. In a few years the railways would thunder into London and gradually steal the canal’s trade.

Footnote