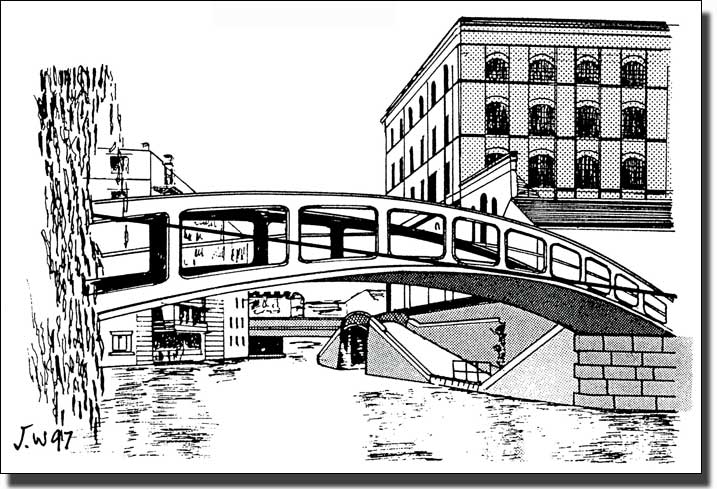

Camden Lock

The Diagonal, or Roving Bridge.

The drawing shows the Diagonal Bridge, with the Interchange Building behind on the right. William Huck’s Bottle Store is on the left. The barge entrance to the Interchange below the towpath is called Dead Dog Hole, for reasons to be made clear later. Regent’s Canal bridges are in all shapes and sizes, some narrowed to take only a single barge, while others are high and free-flying, spanning the valley near the Zoo. By far the best known is the Roving, or Turnabout Bridge, in the middle of Camden Lock. Here one lingers to survey the scene north and south and wonder why such a long bridge was built when a short one would have cost less. All the other bridges go straight across. Why the difference?

The bridge is cast in four pieces. Each side of the bridge consists of two halves, joined at the centre with large bolts. At the ends of the bridge the top rails swell into massive blocks, each of which carries two 1.25 inch diameter steel bars, seen in the drawing above and on the next page. They run from the top of the bridge, but the curvature carries them down to below the footpath at the centre. They are threaded at 12 threads to the inch, a very shallow thread for a bar of this diameter, more like a thread used for a pipe than solid metal. The bars must have been threaded by hand and this shallow thread was the only one available. The whole bridge is an interesting example of engineering before the more powerful machines required by the Railway Age were developed.

But why a diagonal bridge? The answer is in the granite cobbles, steeply pitched to give a grip to horses’ hooves. Each one is polished by wear as if ready for a geologist’s lens. This surface has been produced by a couple of centuries of hard wear by workmen in industrial boots, shod heel and toe with iron studs and especially by the heavy shoes of cart horses, for horses knew this bridge well. The canal towpath is on the left bank only, so consider the problem of moving a mass of horse-drawn barges travelling in both directions, through two locks.

Barges coming down-stream from Regent’s Park were towed by the bargees’ own horses. Tow ropes were released as they approached the locks and the barge still had enough energy for it to be steered into whichever lock was being lowered at the time. On the other hand, barges travelling up-stream were raised by the lock to the level of the Lock Basin but, when they reached the top they had no motion. The barges were still and had to be towed. It was easy to attach a rope to the barges on the left bank, where there was a towpath, and then for their horses to tow towards Paddington. However, the barges which had come up on the right hand lock had to be towed across to the towpath bank, before they could continue their journey. This was the purpose of the Roving Bridge.

There is a short length of towpath on the right bank, but it reaches only as far as the bridge. A horse drew the barge as far as the foot of the bridge. The tow rope was detached, drawn up on the other side of the bridge and re-attached to the horse, which then pulled the barge across to the other bank. The tow-rope dragged against the thick top rail of the bridge and slowly turned the barge against the flow of the canal water. This was hard work and it would have been even more difficult to turn an unwieldy barge if the bridge had been at right angles to the canal. As it was, the pressure on the ropes was so great that the top rail of the bridge and the stones of the canal bank are deeply scored. At some stage an extra protecting bar was added to the bridge, level with the roadway and on the upstream side, to save the bridge itself from similar wear.

|

Grooves worn by innumerable tow ropes on the handrail of the bridge |

Arrived at the towpath side, tow-man quickly unfastened the rope without slowing the boat and threw the rope into the water. With a slap on its flank, he dismissed the horse, which walked back untended across the bridge to the other bank. There it waited patiently to tow yet another barge across the bridge. Meanwhile, the barge horse took over for the level walk to Uxbridge.

This towing problem was so complicated that special horses were used. Ordinary barge horses towed their barges to and from the lock, but at Camden Town the barges had to be worked by specially trained horses. These were so familiar with the routine that they crossed Chalk Farm Road and went down the slope to the lower level, or went back across the Roving Bridge to the southern bank, unattended.

A view from the south bank, with the market beyond